Carlo N. De Cecco

Associate Professor of Radiology and Biomedical Informatics,

Division of Cardiothoracic Imaging, Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging

Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Emory University

Dr. De Cecco is a consultant for/receives institutional research support from Siemens.

Published April 22, 2020

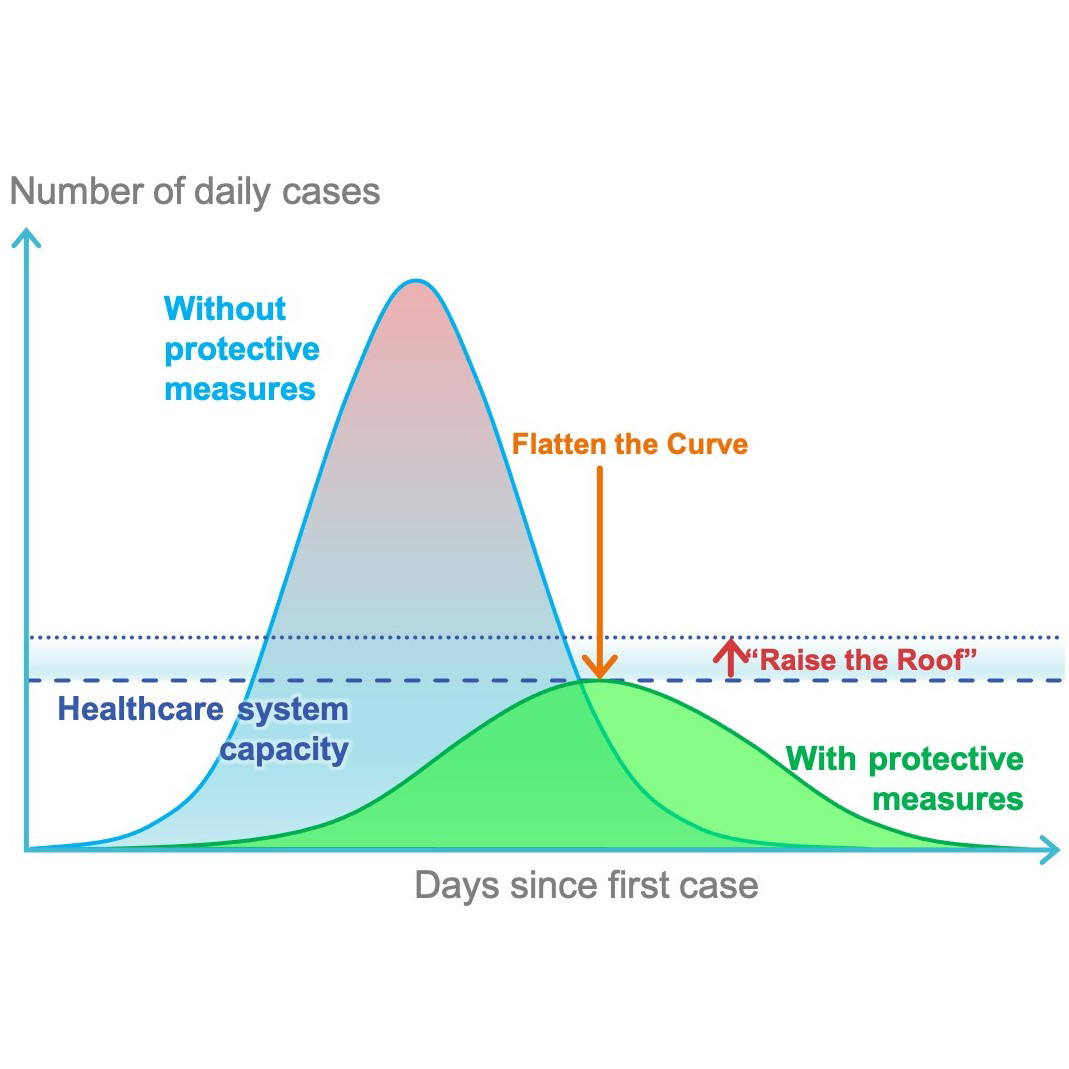

On January 30, 2020, the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was declared to be a global health emergency by the World Health Organization. Four months later, the virus is still spreading all over the globe—more than 3.3 million confirmed cases and 235,000 deaths worldwide—with the United States the most affected nation, numbering more than 1.1 million cases and over 65,000 deaths. Dramatic containment measures have been put into place to halt the diffusion of the virus, yet worldwide health care systems are still struggling with the massive influx of COVID-19 patients.

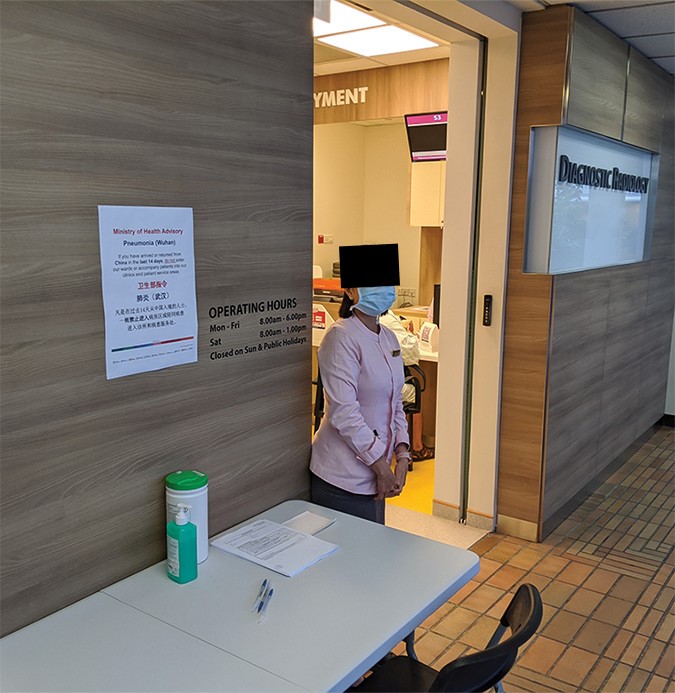

Currently, reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) serves as the gold standard for the diagnosis of COVID-19. However, chest radiography and CT play an important role in the management of patients affected by COVID-19 from diagnosis to treatment response assessment, depending on the clinical situation and particularly in the early days of the outbreak and in specific geographic areas where RT-PCR tests are not readily available. In these situations, chest radiography as first-line imaging and chest CT in complex cases can provide assistance to clinicians by identifying suspicious findings for COVID-19.

Artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms applied to patients with confirmed COVID-19 or subjects under investigation offer the potential to develop a more accurate automated approach for early detection and prognostication using the combination of clinical and imaging data. At the moment, several AI solutions are being developed for application in different stages of the COVID-19 diagnostic workflow, from diagnosis to prognosis.

AI for Classification of COVID-19 Pneumonia

In the early COVID-19 outbreak, radiographic and CT evaluations have been extensively utilized for diagnostic purposes due to their fast acquisition times. AI can be applied to develop algorithms that quickly learn COVID-19 pulmonary patterns from large datasets, as well as using similar manifestations from other types of pneumonia.

Radiography-Based AI Classification

Chest radiography is often used as an initial imaging test. Although generally considered less sensitive than chest CT, chest radiography can provide important information about the pulmonary status of COVID-19 patients, especially in more severe cases. A study by Wong et al. reported that abnormal chest radiographic examinations were found in 69% of patients at admission and 80% of patients at a later time during hospitalization

From a recent review paper, the overall accuracy of AI-based radiographic algorithms for the classification of COVID-19-related pneumonia was pretty good, ranging between 83.5% and 98%

CT-Based AI Classification

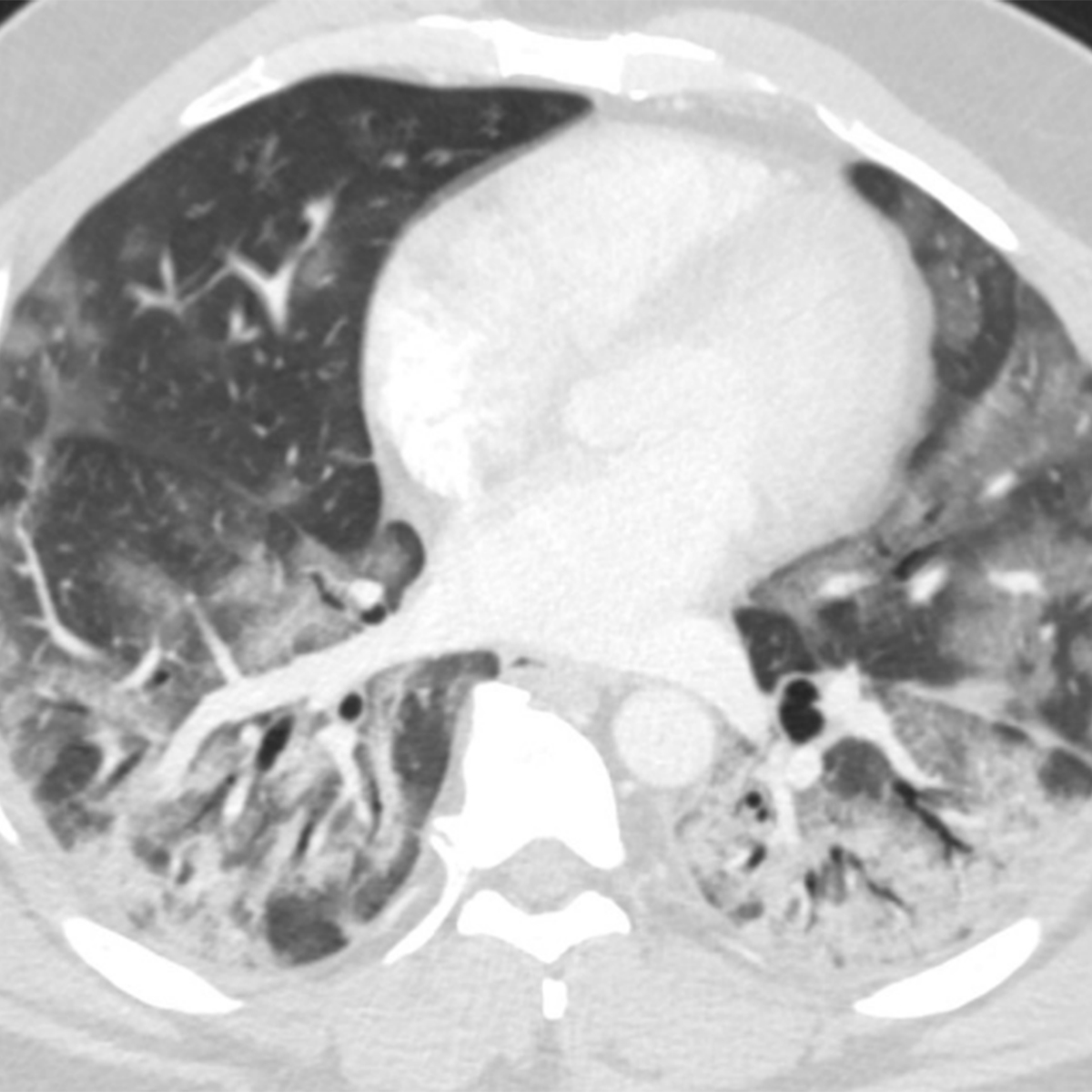

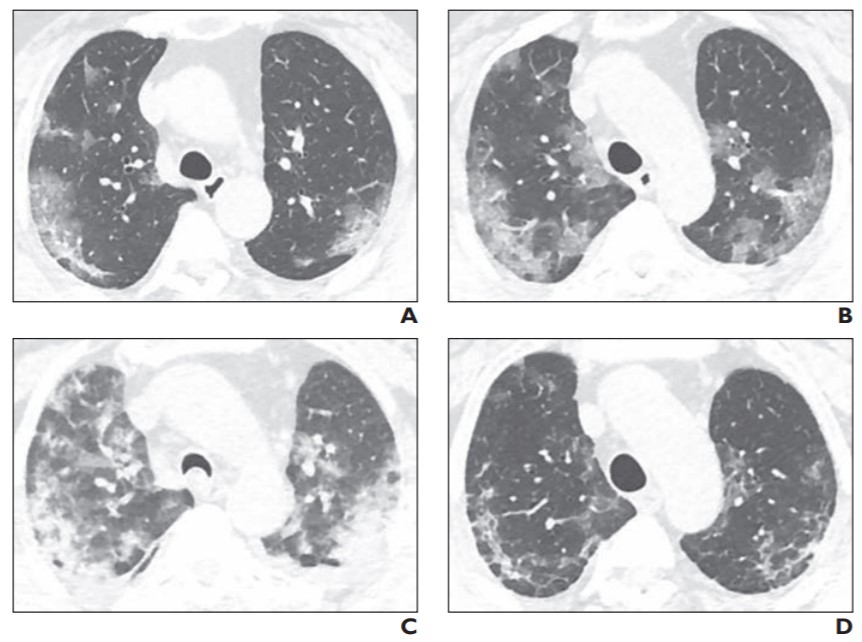

Chest CT images are considered more sensitive for the visualization of COVID-19-related pulmonary manifestations. Several studies have described radiological chest CT patterns, characterizing different stages of the disease. Early signs of the disease are ground-glass nodules, especially subpleural in the lower lobes, which can be found both unilaterally and bilaterally. In the following stages, diffuse ground-glass nodules, “crazy-paving” pattern, and even consolidation can be found, often bilaterally in distribution encompassing multiple lobes

Pan F, Ye T, Sun P, et al. Time course of lung changes on chest CT during recovery from 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia. Radiology 2020 Feb 13 [Epub ahead of print]

Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M, et al. Chest CT findings in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): relationship to duration of infection. Radiology 2020 Feb 20 [Epub ahead of print]

Studies on the AI-based classification of COVID-19-related pulmonary manifestations on chest CT are more prevalent than the ones on radiographic images. One of the largest studies performed by Shi et al.

AI Prediction of Disease Severity and Progression

With increasing laboratory test availability for COVID-19 diagnosis, the focus of medical imaging is shifting to the assessment of disease severity and disease progression, which can be used for treatment planning optimization and treatment efficiency evaluation

Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M, et al. Chest CT findings in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): relationship to duration of infection. Radiology 2020 Feb 20 [Epub ahead of print]

Zhao W, Zhong Z, Xie X, Yu Q, Liu J. Relation between chest CT findings and clinical conditions of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia: a multicenter study. AJR 2020 Feb 19 [Epub ahead of print]

Li K, Wu J, Wu F, et al. The clinical and chest CT features associated with severe and critical COVID-19 pneumonia. Invest Radiol 2020; 55:1

Li M, Lei P, Zeng B, et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): spectrum of CT findings and temporal progression of the disease. Acad Radiol 2020; 27:603-608

A study by Huang et al.

Emory AI Project: The PREDICTION Study

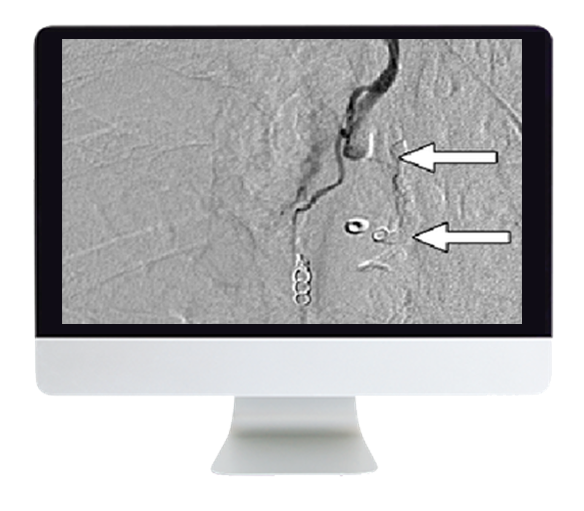

At Emory University, in collaboration with the Georgia Institute of Technology, we have started an AI project on COVID-19, entitled “Predictive Model of COVID-19 Outcome Using a Convolutional Neural Network Applied to Chest Imaging and Clinical Parameters: Early Detection and Prognostication for Optimal Resource Allocation (COVID-19 PREDICTION Study)” (Fig. 1).

We have two objectives:

- Use supervised learning methods to build a predictive model that can distinguish COVID-19 pneumonia from other common lung pathologies using chest imaging and clinical parameters.

- Monitor the disease progression over time detecting different evolution patterns, ideally finding imaging and clinical parameters that can predict the evolution to the most severe cases of COVID-19, which result in intensive care unit admission and the need for respiratory assistance.

With this project, we hope that an AI-powered solution for COVID-19 early detection and prognostication will have a major impact on patient outcome and optimization of the resource allocation, in particular in areas with limited medical resources and access to ventilators.

Future Developments and Perspective

In the near future, more AI-based solutions will be developed and applied for the evaluation of COVID-19 using medical imaging. Whereas the first AI approaches were mostly focused on COVID-19 diagnosis, we now see more algorithms focusing on disease severity and progression quantification. The first step for the development and training of these AI algorithms is the creation of large, representative databases, followed by proper algorithm validation. At the moment, there are several worldwide initiatives for the creation of open-source databases for both radiographic and chest CT images

Cohen JP, Morrison P, Dao L. COVID-19 Image Data Collection. arXiv website. arxiv.org/abs/2003.11597. Published Mar 25, 2020. Accessed May 7, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic presents an exceptional challenge for the international health care community. The social impact has been dramatic and will be lasting. Although no country was fully prepared at the beginning of this pandemic, we can now use the lessons learned—together with the large volume of generated clinical data and developing AI techniques—to prepare more efficient global response strategies.