Jonathan Kruskal

2021–2022 ARRS President

Published July 28, 2021

During this year’s virtual and highly successful American Roentgen Ray Society meeting, it became apparent that we are living in a time of accelerated development and deployment of existing and emerging digital technologies. Individuals and teams are using innovative solutions to care for patients, teach trainees, collaborate with colleagues, and connect within an expanding digital universe.

I for one never imagined that my weekly mobile COVID-19 prediction report would include hourly population densities in nearby airports, supermarkets, restaurants, and bars. With geographically traceable devices, what data could possibly be next?

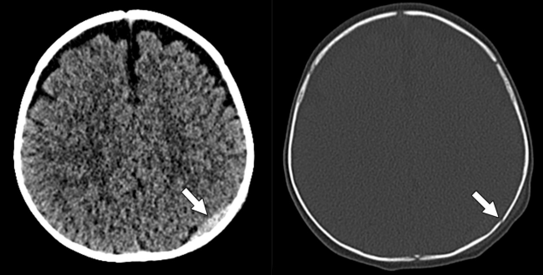

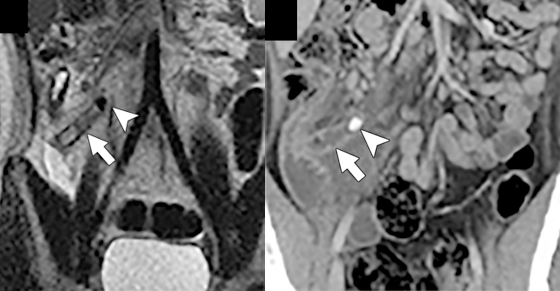

In the same way that NASA’s Apollo program sparked the development of new technologies (many of which were largely realized and appreciated years later) that landed the first humans on the moon, we are witnessing a fundamental transformation in health care operations that will be captured in future history books. Few could have predicted, for example, that CT scans would become an indispensable screening, diagnostic, staging, and management tool during a global pandemic. Providers have harnessed such a wide swath of tools—from laptops, mobile and wearable devices, and video conferencing to artificial intelligence, thermal sensors, and robots—to better serve patients and their loved ones, sustain remote reading and teaching environments, and uphold compliance and safety protocol. We now achieve efficiencies through rapid scanning, recruit new faculty through social media, teach our trainees in cloud-based classrooms, and attend national conferences with just a click—all without ever boarding a plane or even crossing clinical campuses.

The Future Is Now

The evidence shows that embracing digital technologies results in improved patient outcomes, cost savings and efficiency, increased productivity, heightened compliance and safety, transformed teaching methods, stakeholder satisfaction through digital connections, sustained remote teams, and accessible employee communications and wellness initiatives.

Previously, such innovation resided primarily within the hospital and physician domains, with the gradual integration of patients as they began accessing their personal electronic health records. Now, our digital stakeholders include not only patients, but referring providers, remote teams, educators and learners, researchers, public health authorities, policymakers, schedulers, transporters, the public, commuters, and travelers.

And as the digital stakeholder pool expands, so does its impact: Such technologies now routinely support telehealth, data analysis, access, scheduling, and follow-ups, management decision-making, bidirectional communication, safety compliance and practices, PACS enhancements, teaching and readouts, patient monitoring, diagnostics, consulting, screening, training, forecasting, reporting, and, of course, socializing.

Examining Digital Disparities

We must remember that our digital environment is far from globally universal. At-risk, vulnerable, underserved, and marginalized populations, such as those living more than 7,600 miles away in India today, are grappling to secure simple access and connect effectively with providers and health care delivery services through traditional means, let alone digital ones. They desperately need hospital beds, oxygen and plasma, life-saving vaccine doses, and medical workers. Resources that hospitals, such as ours, are so fortunate to have readily on hand. However challenging these issues are to address, such disparities in access, care, and connections must be studied and included in the many national efforts aimed at eliminating them. What a terrific opportunity for us to make a meaningful difference that matters.

To a large extent, this digital divide is driven by equality, equity, and justice, or the lack thereof. With equality, we assume that here in Massachusetts, for example, all of our patients benefit from the same supports. All are treated equally, irrespective of any differences. But this isn’t necessarily true yet. Having a laptop certainly doesn’t mean a patient can easily access and understand one’s medical records. Additionally, not all laptops have video cameras, and not all hardware supports the ability to participate in video conferencing or telehealth solutions. And then there are those patients who don’t have access to a laptop to begin with. Where does that leave them? It is our responsibility to find out.

From the perspective of equity, everybody receives the specific and different supports they need and, therefore, receive equitable treatment. This is closely tied to justice (some view this as liberation); our underserved patients receive access to appropriate care without requiring specific accommodations because the fundamental causes of inequities have been addressed. In other words, the preexisting systemic barriers have been effectively identified and removed. Consider the impacts and barriers that may exist due to language, poverty, mobility, cognition, geography, access to water, electricity, food, transport, comorbidities, and employment status. By working to eliminate or flatten these barriers, care becomes more equitable and just. There are innumerable opportunities for making a difference that matters here, starting locally.

Bridging Local Gaps

Consider your own imaging team: When you hold video meetings, do all members have equal access to the necessary hardware and software to participate effectively? Are all members afforded the same privacy and time to participate in these meetings? This lesson was brought home to us when we recently convened a video meeting of our wellness council and noticed that several of our technical and nursing staff did not have access to video equipment in their workplace.

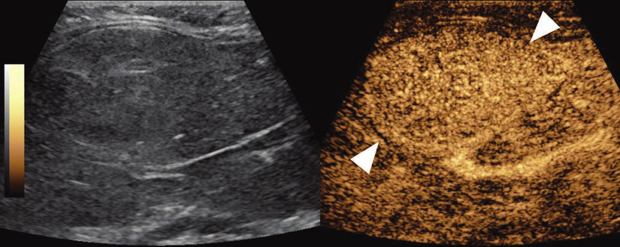

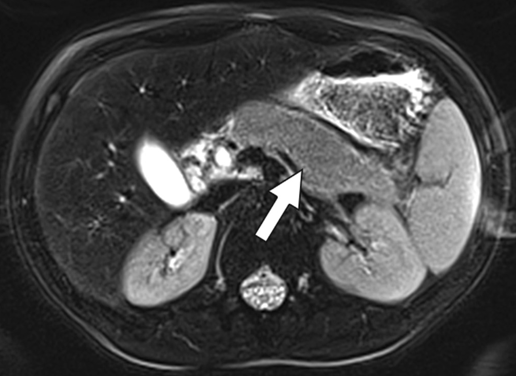

Consider your patients, as well: While a health care system might deploy sophisticated software to support their telehealth endeavors, this does not mean that all patients have the necessary hardware or software to participate. Additionally, solutions to barriers such as vision, language, and hearing must be readily available. One additional effort I applaud is to make our digital reports more comprehensible; not every patient understands what is meant by the phrase “the hepatic parenchyma demonstrates a normal echotexture,” nor should they. We should support software solutions to simplify the communication and accuracy of our recommendations.

And in keeping with our educational mission, think about the brisk implementation of so many solutions to support ongoing academic efforts. Will we ever return to our traditional morning resident teaching conference? I’d imagine not; if anything, the pandemic will finally allow us to move away from the prolonged didactic and synchronous teaching methods to ones that are more appropriate, personalized, and contemporary.

Another essential pillar of academic radiology is teaching and developing the next generation of radiology leaders during readouts. We seem to be mired in surveys and comparisons about what processes work best for our traditional readouts. Let’s instead open our eyes to completely new and asynchronous approaches. What an opportunity! And last within this category is lifelong learning. The necessary transformation to virtual national academic meetings this past year has demonstrated the many advantages that our digital environment offers for such forums. Be it cost savings for participants and practices, wider availability of CME credits and on-demand content, less time away from the workplace, or and the ability to directly connect with speakers, the benefits are plentiful.

Keeping Our Imaginative Focus

Where the opportunities lie here are in fostering participant connections and rethinking how we should transform the content, styles, and media of our traditional talks to take full advantage of individual learner needs and preferences. Again, what terrific opportunities exist in this domain!

So, where do we go from here?

While tremendous and necessary strides have and continue to take place in our abilities to communicate, manage, and connect remotely, I only ask that we continue to be mindful and considerate that not all stakeholders are currently able to participate equally and effectively. The phrase “you’re only as fast as the slowest member of your relay team” is so apt nowadays. In our digital environment, the concept of “precision medicine” should now expand to embrace the specific needs and preferences of our many stakeholders.

As we continue to build and expand our digital frontend, it is equally necessary to focus on supporting the backend, so that all of our team members and stakeholders can participate and benefit from the systems and solutions that are being deployed. The opportunities here are endless, and we need to develop, implement, and share solutions that will ultimately meet the needs and improve the outcomes for our patients. Let’s please keep our imaginative focus on why we entered this wonderful, exciting, and ever-expanding field of radiology in the first place.