Daniel Ortiz

Muscoloskeletal Radiologist, Summit Radiology Services, P.C.

Social media has been labeled by many as “the great equalizer,” but the truth is that it does so much more than equalize. Prior to social media, both physicians and the public kept their networks local—that is their communities, institutions, and departments—and few opportunities existed to branch out and become known, namely through scholarly work and national organization meetings. Outside of these venues, ideas were left to echo through halls in isolating silos, suppressing opportunities for robust discussion, diversity of thought, and innovation.

Since the advent of social media, the medical world has slowly broken down long-standing barriers that have separated us from each other. Never before had it been possible for medical students and trainees to have such easy access to meaningful interactions with top radiology leaders from across the country, around the world even. Moreover, frequent social media micro-exposures have served as invaluable icebreakers, making an initial in-person meeting easier for introverts and more enjoyable during high-stake interactions, especially where a hierarchical difference exists.

As data becomes more plentiful, online users have opted to consume new knowledge in brief, high-yield microbursts. Although there will always be a need for deep and thorough dives into a subject, much of what we need to know can be summed up in small packages. This consolidation has led organizations and journals to accommodate the style of consumption through tools such as infographics that capture the attention of the viewers and provide them with the salient points. This stimulating, digestible format has the potential to increase readership and improve retention. Usually, these tools are paired with links back to the organization’s website or journal for expanded content.

Each social media platform has unique features, but within the radiology community, Twitter stands out as the preferred media for developing a professional online presence, thanks to their 280-character restriction, unilateral following feature, and browsable format. The image-driven Instagram is another favored medium but does not have Twitter’s same character restriction. Facebook can be used to post similar messages, but it may be more amenable for lengthier, blog-style posts.

Radiology education (#raded) is particularly amenable to image-rich platforms, and many organizations and academic departments are shifting educational content to social media, particularly Instagram and Twitter. This content is commonly curated using the searchable hashtags #FOAMed (free open access medical education) or #FOAMrad (free open access medical education radiology). Much in the way of traditional, in-person radiology teaching, educators post representative images of radiological findings, employing various methods to interact with viewers. Some encourage viewers to respond to the posting in the reply section with their perceived answer. Others provide a link to a website with a response form, allowing the poster to easily store replies while giving respondents an opportunity to reply anonymously (i.e. #EmoryRadCOTD).

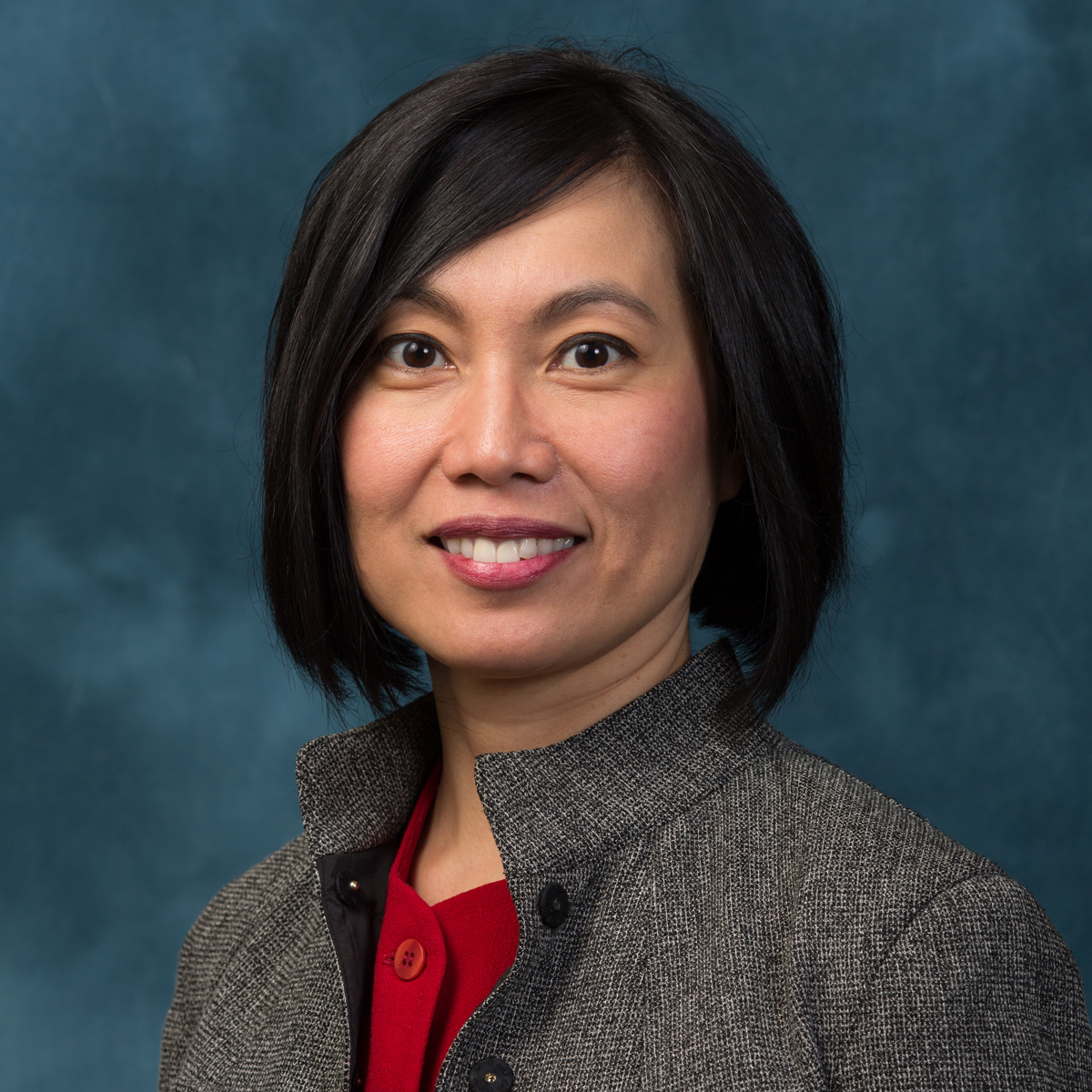

Several of the nation’s leading radiology educators have been using Twitter and Instagram to broaden their impact on students and colleagues. Started in 2016 by Geraldine McGinty (@DrGMcGinty) and Mini Peiris (@Mini_Peiris), #radxx is an initiative focused on advancing women in various disciplines related to medical imaging, particularly informatics. Michele Retrouvey (@MRetrouvey) has explored the challenges women in radiology face finding other female mentors and how social media could be used to provide a global network of mentors. Meanwhile, some authors are even advocating for social media impact in academic promotion.

Outside of standard education, implementing a successful Twitter presence has taken on many forms for different cohorts. Super-users like Rich Duszak (@RichDuszak), María Díaz Candamio (@Vilavaite), and Ian Weissman (@DrIanWeissman) curate and share interesting news articles, whereas other creative users have opted to harness the full novelty of the platform. Nicholas Koontz (@nakoontz) gamifies education by responding to cases in the form of a GIF. Others like William Morrison (@morrisonMSK) provide a more artistic side of radiology, pairing medical imaging with similar real-world objects.

Many radiology organizations are starting to publish periodic cases, such as the ARRS Case of the Week or the Society of Skeletal Radiology’s Annual Meeting Case of the Day Collection under the hashtag #SSRBONE19COD. In 2017, Vivek Kalia (@VivekKaliaMD) wrote an in-depth article discussing how radiology meeting organizers and attendees can leverage Twitter to maximize the meeting experience.

Beyond interacting with other physicians and students, social media provides the opportunity for radiologists to connect with other specialties, patients, and patient advocacy groups. Some of the most active advocacy efforts on social media are breast health (#mammosaveslives, #stoptheconfusion, #bcsm), colon cancer screening (#virtualCT), and lung cancer (#lcsm). Given the ubiquity of social media in society and the decline in time clinicians can dedicate to patient education, social media stands to be one of the most open and potentially “viral” ways to transmit critical medical information and breakthroughs to the public. A platform for experts to correct misinformation being shared, social media also allows physicians to see the perspectives of patients and advocates (such as Andrea B. Kitts, @findlungcancer) which they may not have been exposed to otherwise. This is particularly true of TweetChats—pre-planned, scheduled, and moderated conversations on a focused topic. TweetChats are open for public discussion and lead to robust, diverse discussions and profound takeaways that can only be incubated in the inclusive environment that social media provides.

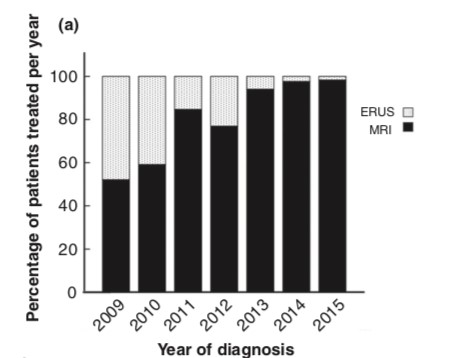

In 2015, McKinley Glover looked at social media use among the largest private radiology groups and academic radiology departments and found that 76% of private groups and 28% of academic departments had at least one social media account. Outside of medicine, businesses understand being visible to potential clients where they spend their time is one of the best ways to increase foot traffic, and Statista estimates that $19.3 billion was spent on social media advertising in 2018. Private and academic practices alike, if they use social media effectively, can increase the number of patients that choose them for their health care needs by advertising the services they provide and giving a “face” to their practice. Through a combination of local news spots and social media, Amy Patel (@amykpatel) saw a large spike in her private practice mammography clinic after implementation.

The most effective social media strategy requires active participation of the physicians, as well as ancillary staff with training and experience to help administer the account and post on a more frequent basis. In discussions with social media-averse colleagues, two reasons for non-engagement stand out. First is the time commitment to be active. Social media super-users dedicate a lot of time to engagement, but most users take a more moderate, peripheral approach. However, even if someone does not post frequently, just being passively exposed to the content on social media can be rewarding and informative. There is no minimum or maximum for social media engagement. Ultimately, the user decides what type of content is seen on any feed by tailoring who he or she follows. As the user becomes more acquainted with the platform and culture, the bar for jumping into informative discussion gets lowered.

The second reason radiologists cite for not engaging in social media is the perceived loss of privacy. As one colleague put it, “I don’t want another way for people to get a hold of me.” Again, Twitter has customizable features that allow the user to prevent unsolicited tags, tweets, and direct messages. As with any form of networking, there is an initial uneasiness meeting new people, but social media can help minimize that feeling. There are benefits to branching out, of course. A mentor once told me: “You don’t have a network if you only interact with people from your institution.”

A hesitant and relatively late adopter (April 2016), I have since found social media—particularly Twitter—to be a beneficial tool for my professional development. I often learn about advancements in radiology through social media well before more traditional media outlets and communication channels. Furthermore, I have seen medical students and residents connect via social media with mentors from other institutions, and then continue their training under those mentors later in their career. As our community becomes more interconnected via social media, for both networking and education, I believe we will approach a tipping point where a professional social media presence and “brand” will become more expected of individual physicians and practices.

If you are interested in exploring a Twitter presence, I encourage you to read Rich Duszak’s basic primer on the subject on the Journal of the American College of Radiology’s blog. I hope to see you soon on the #Twittersphere!

The opinions expressed in InPractice magazine are those of the author(s); they do not necessarily reflect the viewpoint or position of the editors, reviewers, or publisher.