Stacy J. Kim, MD

Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology

Washington University in St. Louis

The first human lung transplant was performed in 1963. Since then, the number of lung transplant cases in the United States has steadily increased due to continued advancements in surgical technique and immunosuppressive medication. There were over 3000 lung transplants performed in the United States in 2023, and the number of lung transplants is likely to continue to increase [1]. The patients who undergo lung transplant are those with end-stage lung disease, which can result from a variety of pathologies including emphysema, fibrosing interstitial lung disease, cystic fibrosis, and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Postoperatively, these lung transplant recipients are vulnerable to complications for the remainder of their lives. The complications can be categorized by time course; that is, the time period after transplant during which the complications occur or most often occur.

The postoperative time periods can be organized as follows: immediate, within 24 hours of transplant; early, from 24 hours to 1 week after transplant; intermediate, from 1 week to 3 months after transplant; and late, more than 3 months after transplant [2]. Some complications can occur during more than one time period or span multiple time periods. This chapter will discuss the complications that occur or most often occur during the 1st month or so after lung transplant, which includes immediate, early, and some of the intermediate complications. Late complications of lung transplant will be discussed during the 2025 ARRS Annual Meeting Categorical Course, “Comprehensive Insights Into Transplant Imaging,” in San Diego, CA, and online April 27-May 1.

Imaging Techniques

Chest radiography is the most commonly used imaging study in the immediate and early postoperative setting. Chest radiographs are easy to acquire at the bedside and are useful in evaluating the positions of tubes and lines, which are ubiquitous immediately after transplant, such as endotracheal tubes, central venous catheters, and chest tubes. The lung parenchyma and the pleura can also be evaluated with chest radiographs for complications such as pneumonia and pleural effusion. Given the lower radiation dose of chest radiography when compared with CT, chest radiographs are useful for serial imaging; that is, image acquisition over multiple days to assess for change over time.

CT of the chest is performed if a more detailed assessment of the chest is required. Example scenarios in which a detailed assessment may be necessary include if there is concern for bronchopleural fistula in the setting of a persistent pneumothorax, if a pulmonary embolism (PE) is suspected due to new-onset tachycardia, and if a patient with decreasing hemoglobin values must be evaluated for hemorrhage. A noncontrast chest CT examination is sufficient for evaluation of the lung parenchyma, airways,

and bones. A contrast-enhanced chest CT examination should be acquired (if the patient’s renal function permits and if the patient does not have a contrast media allergy) for evaluation of the vasculature and the pleura and assessment for active hemorrhage. The protocol or phase of contrast should be tailored to the diagnosis being evaluated; for example, a PE protocol should be used when evaluating for PE.

A noncontrast high-resolution chest CT examination is rarely necessary for the evaluation of early lung transplant complications. However, it is useful for the evaluation of late lung transplant complications as it can be used to detect air trapping and fibrosis (discussed in the next chapter). MRI, sonography, and nuclear medicine imaging are not typically used in the evaluation of early lung transplant complications.

Hyperacute and Acute Rejection

Hyperacute rejection occurs during the lung transplant surgery or within 24 hours of transplant when preformed recipient antibodies react to donor antigens in the allograft [3]. It is exceedingly rare because ABO blood group antigens and human leukocyte antigens are taken into account when lung donation is arranged, to ensure donor-recipient compatibility. Hyperacute rejection manifests as fulminant multiorgan system failure, and most patients with hyperacute rejection die within a few days to 2 weeks after lung transplant. The imaging findings of hyperacute rejection are nonspecific and resemble severe pulmonary edema, including consolidation, ground-glass opacities, and septal-line thickening.

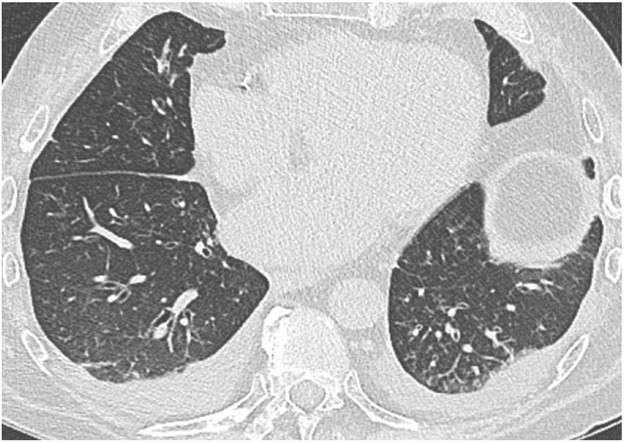

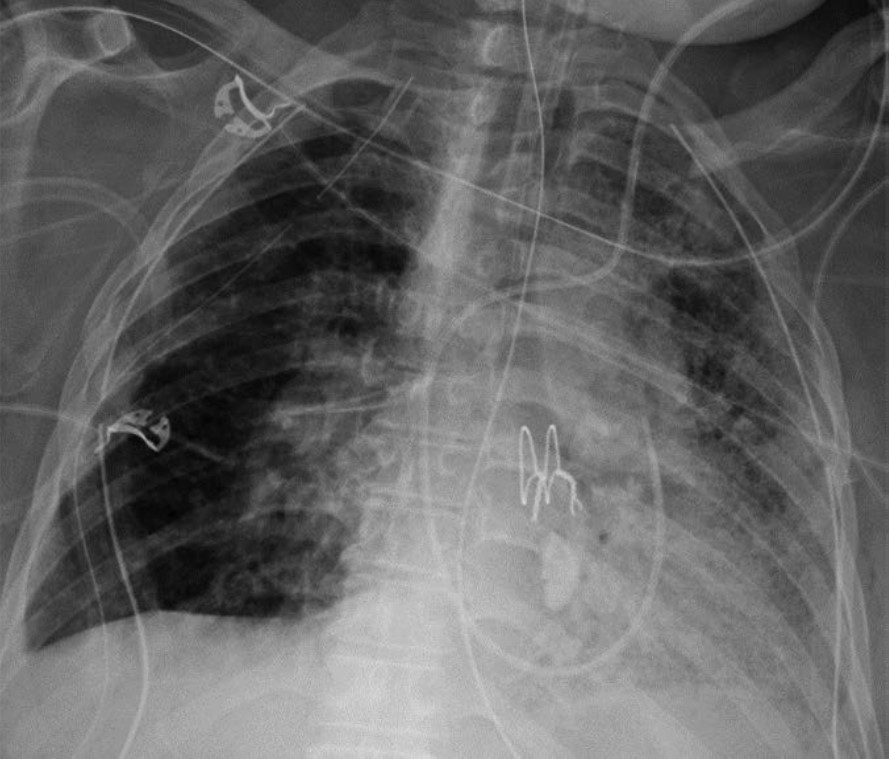

Acute rejection can occur anytime after lung transplant. It consists of two types, acute cellular rejection (ACR) and antibody-mediated rejection (AMR), which can coexist. ACR is the more common of the two types and occurs when recipient T lymphocytes attack donor antigens within the lung allograft. Approximately 35% of lung transplant recipients experience at least one episode of ACR during the 1st year after transplant [2]. During these episodes, patients may be asymptomatic or may present with nonspecific symptoms such as dyspnea and cough. The imaging findings of ACR are nonspecific and include consolidation, ground-glass opacities, and septal-line thickening; as with hyperacute rejection, ACR resembles pulmonary edema. Given its nonspecific clinical and imaging manifestations, ACR requires transbronchial biopsy and tissue analysis for diagnosis. Timely treatment, typically by increased immunosuppression with steroids, is important because ACR is the greatest risk factor for chronic lung allograft dysfunction [4]. Figure 1 shows a patient with biopsy-proven ACR.

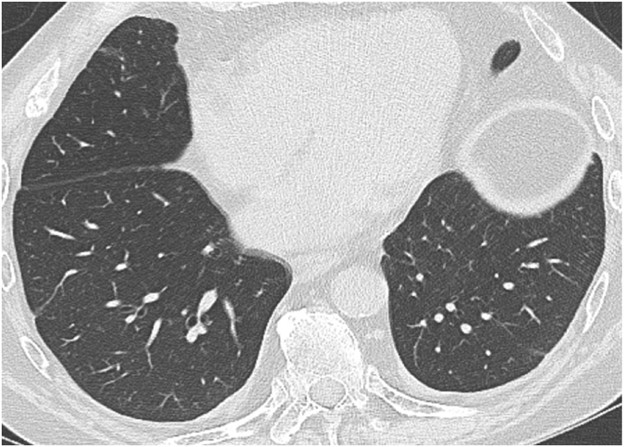

AMR, the less common of the two types of acute rejection, occurs when recipient B lymphocytes create donor-specific antibodies (DSA), donor-specific antigens and DSA form complexes, and the complexes trigger the immune system’s complement pathway. Like patients with ACR, patients with AMR can be asymptomatic; can have nonspecific symptoms such as dyspnea and cough; and can have normal chest imaging or nonspecific imaging findings resembling pulmonary edema such as consolidation, ground-glass opacities, and septal-line thickening. Transplant physicians diagnose patients with clinical versus subclinical AMR and definite versus probable versus possible AMR on the basis of the presence or absence of allograft dysfunction, histology results suggestive of AMR (such as neutrophil arteritis and capillaritis), immunostaining results (positive C4d staining of the capillary endothelium), and the presence or absence of DSA in peripheral blood [4]. Treatments include plasmapheresis and IV immunoglobulin to remove harmful antibodies and to suppress antibody production, respectively. Steroids are not typically used to treat AMR, unlike ACR. Figure 2 shows a patient with AMR.

Primary Graft Dysfunction

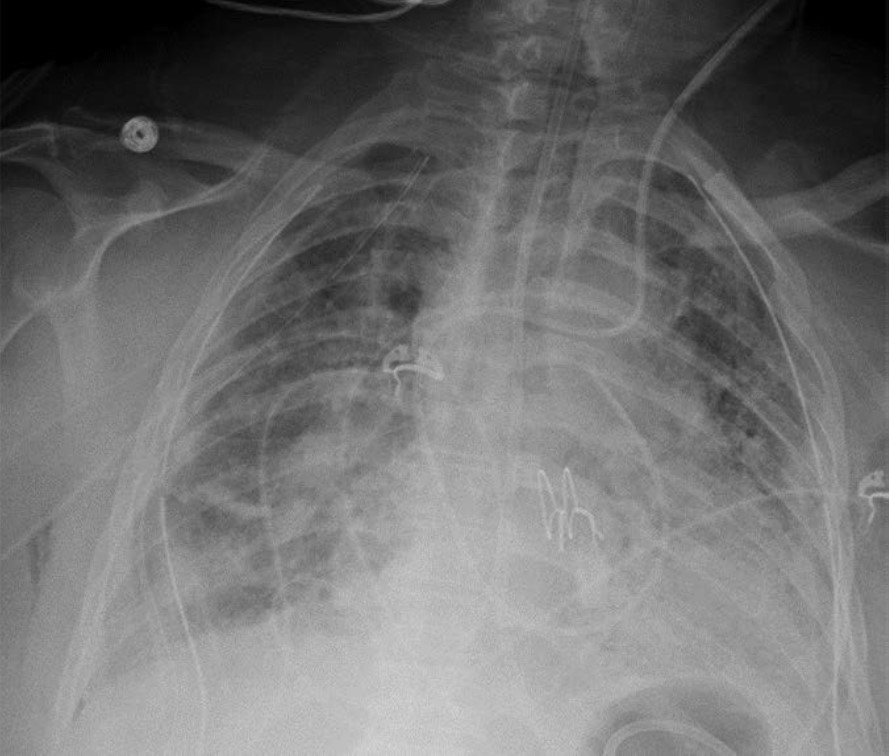

Primary graft dysfunction (PGD) is a transient complication that occurs within 24–72 hours after lung transplant and tends to resolve by postoperative day 5–10. PGD is thought to be secondary to ischemic injury of the allograft before and during transplant and secondary to reperfusion injury after transplant. PGD occurs in approximately 10–30% of lung transplant recipients [5]. On imaging, it manifests as perihilar and lower lung–predominant airspace and interstitial opacities and is similar in appearance to pulmonary edema. Clinically, PGD is graded from 0 to 3 on the basis of the presence or absence of imaging abnormalities and the severity of hypoxemia [6]. In patients who have undergone a unilateral lung transplant, PGD and pulmonary edema can be differentiated by observing the distribution; PGD affects only the lung allograft, whereas pulmonary edema affects both the lung

allograft and the native lung. Like acute rejection, PGD is considered a risk factor for chronic lung allograft dysfunction. It is treated with supportive care, such as mechanical ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Figure 3 shows a patient with PGD.

Infection

Infection of the lung parenchyma and airways is exceedingly common after lung transplant due to immunosuppression and decreased mucociliary clearance in the airways after transplant. Infection can occur anytime after transplant, including the early postoperative period. Patients are vulnerable to bacterial pneumonia as well as viral and fungal pneumonias not commonly encountered in immunocompetent patients. Common pathogens include Pseudomonas organisms, Staphylococcus aureus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex virus, Aspergillus organisms, and Candida organisms [2].

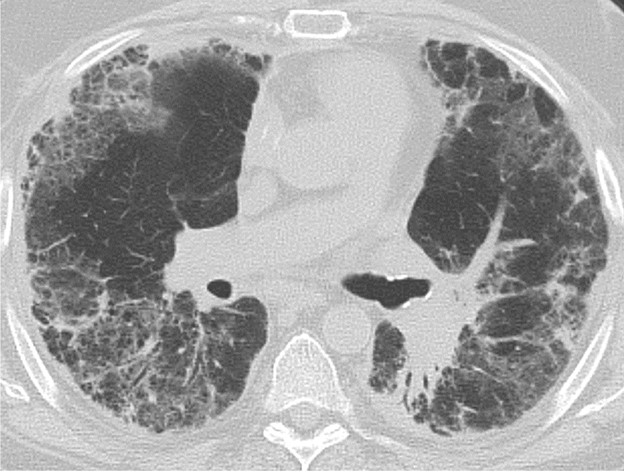

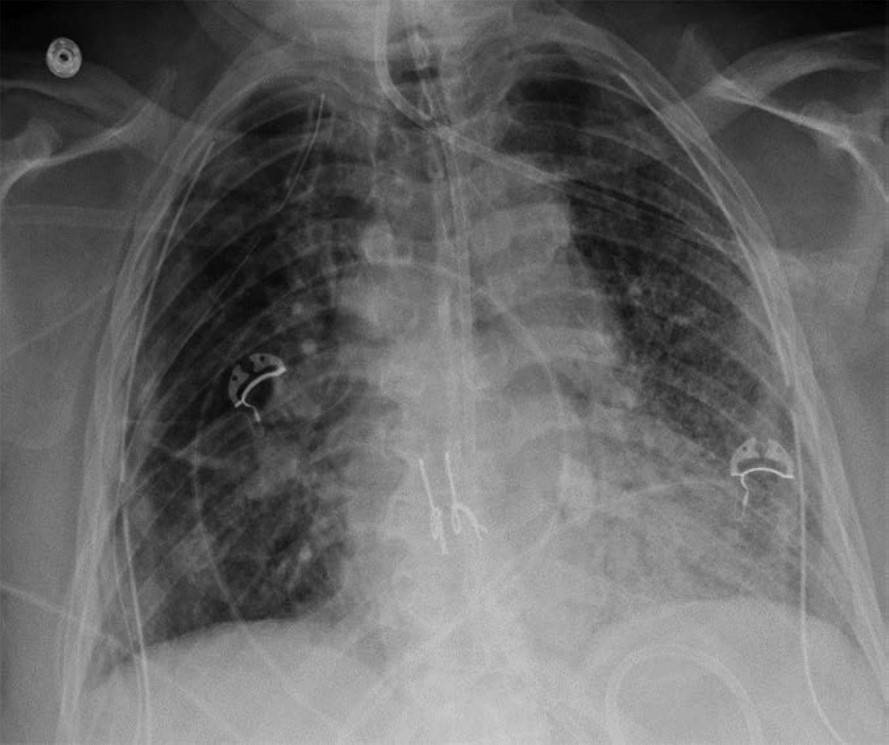

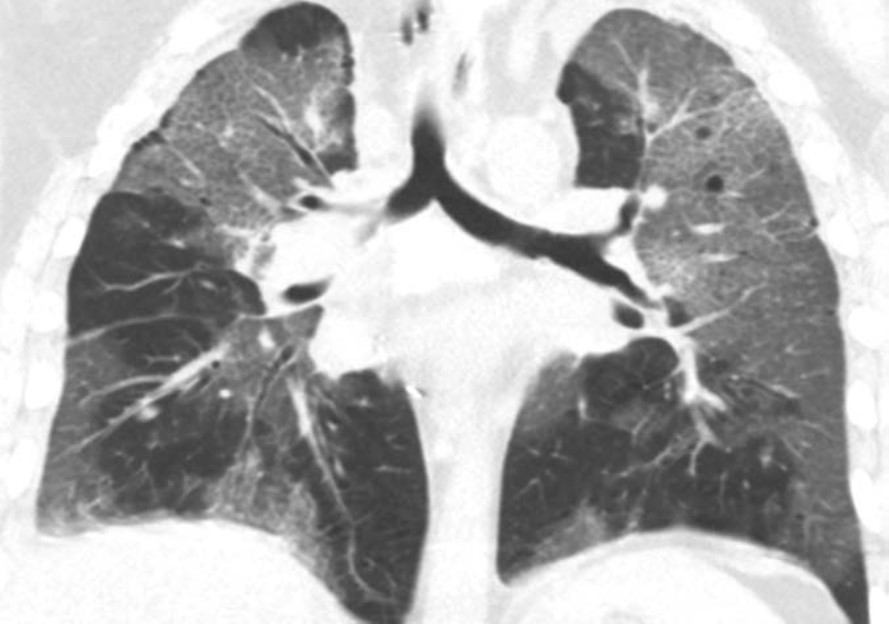

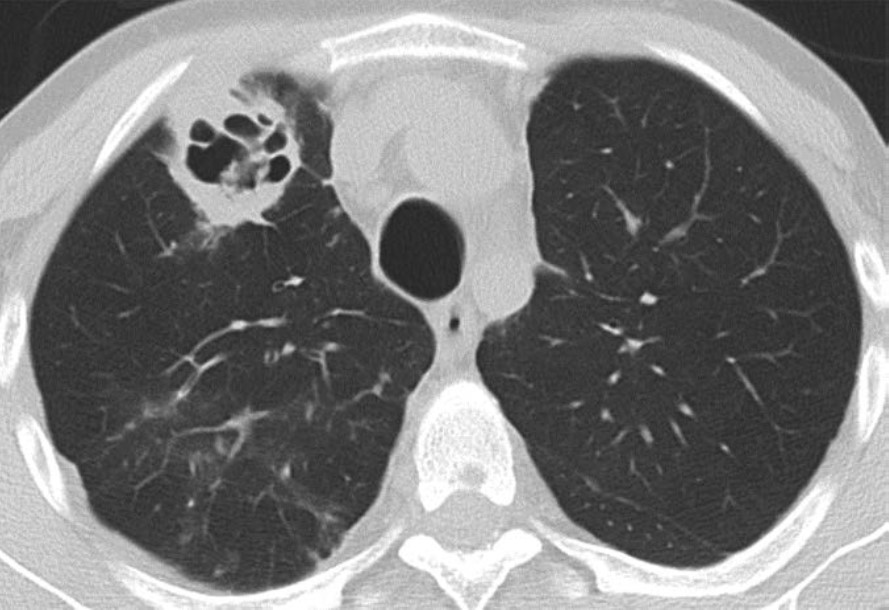

The clinical and imaging manifestations of pneumonia in transplant recipients are similar to those of nontransplant patients. Lung transplant recipients who present with dyspnea, cough, or fever are evaluated for pneumonia. Imaging findings of pneumonia include consolidation, ground-glass opacities, septal-line thickening, and pulmonary nodules. Pulmonary nodules can be single or multiple; they may be solid or ground-glass in attenuation. Cavitary nodules and nodules with ground-glass halos can occur, especially in patients with fungal pneumonia. Imaging studies should be scrutinized for complications of infection such as pulmonary abscess and bronchopleural fistula. Patients may also have reactive pleural effusions or reactive mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy. Treatment is the same as in nontransplant patients and consists of antibiotics, antivirals, or antifungals depending on the causative pathogen. Figure 4 shows three different lung transplant recipients with pneumonia.

Pleural Complications

Simple pleural effusions and small pneumothoraces are frequently encountered in the immediate and early posttransplant setting and typically resolve within a few days to 1 week or so after lung transplant. Pleural fluid collections and pneumothoraces that are large, increasing in volume over time, or persist over 1 week may indicate a potentially serious complication such as hemothorax, empyema, bronchial anastomotic dehiscence, or bronchopleural fistula.

Hemothorax, the presence of blood products in the pleural space, should be suspected if there is rapid increase in the volume of pleural fluid over serial imaging or if pleural fluid is hyperattenuating relative to simple fluid on CT. Hemothorax can be heterogeneous in attenuation on CT due to mixing or layering of new blood products with old blood products; a fluid-fluid level may be present. Figure 5 (left) shows a patient with hemothorax.

Empyema, the presence of infected material (i.e., pus) in the pleural space, should be suspected if there is persistence of pleural fluid over serial imaging for more than 1 week or so after transplant and if visceral and parietal pleural thickening or loculated pleural fluid is present on chest CT. On contrast-enhanced CT of the chest, patients with empyema may have abnormal thickening and enhancement of the visceral pleura and parietal pleura with fluid between the two pleural layers, which is known as the split pleura sign. Figure 5 (right) shows a patient with empyema.

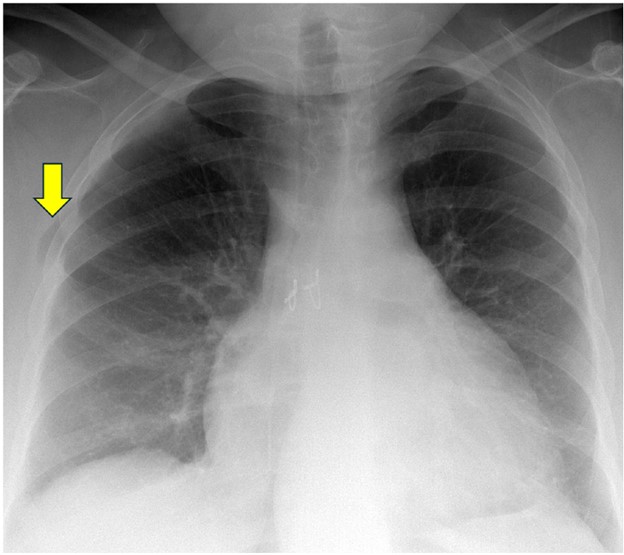

Pneumothorax, the presence of gas in the pleural space, may be indicative of a bronchial anastomotic dehiscence or a bronchopleural fistula if it persists more than 1 week after transplant or increases in volume over time. A tension pneumothorax with cardiomediastinal shift away from the affected hemithorax should be immediately communicated to the transplant medicine team, as an untreated tension pneumothorax can cause cardiovascular and respiratory collapse. Small pneumothoraces on immediate postoperative chest imaging that resolve over the next few days, at which point any chest tubes present would be removed, are considered to be expected postoperative findings.

Treatment of pleural collections typically involves drainage of the pleural space material via pleural catheters or thoracostomy tubes. Surgical intervention may be required if drainage via catheters and tubes is unsuccessful or if the pleural collections are caused by complications such as bronchial anastomotic dehiscence or a bronchopleural fistula.

Vascular Complications

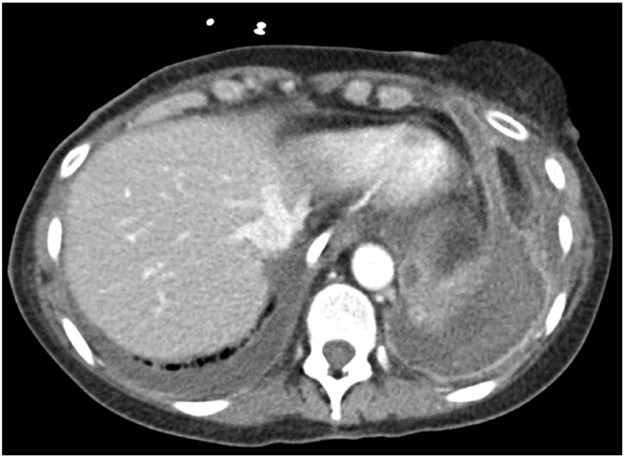

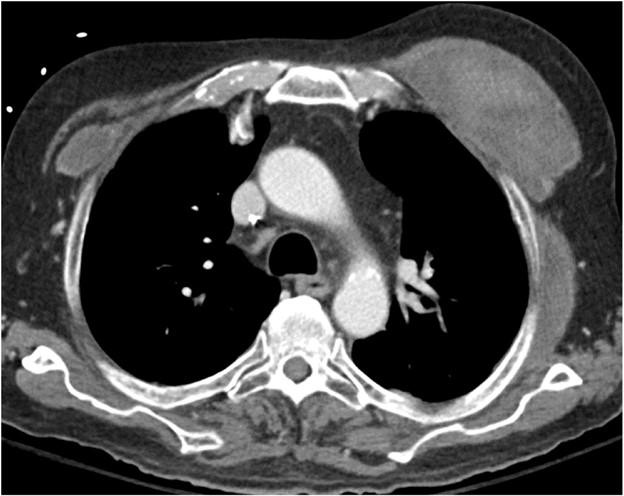

PE can occur after lung transplant. Hemorrhage most commonly occurs during the immediate and early postoperative periods and can manifest as hemothorax, other forms of thoracic hemorrhage such as mediastinal hematoma and chest-wall hematoma, and nonthoracic hemorrhage such as retroperitoneal hematoma. Approximately 4.5% of lung transplant recipients experience posttransplant hemorrhage severe enough to require surgical intervention [7]. The causes of hemorrhage include inadequate coagulation, vascular anastomotic dehiscence (which is rare but can be catastrophic when it occurs), and injury of other vessels. CT of the body part of concern (for example, CT of the chest if there is concern for mediastinal hemorrhage) should be performed, ideally with IV contrast material. If active hemorrhage is suspected, CT can be performed before and after the administration of IV contrast material in the arterial and venous phases to detect contrast material extravasation.

PE also most commonly occurs during the immediate and early postoperative periods. Patients are typically bedbound for at least the first few days after lung transplant, and some patients require mechanical ventilation during that time. Some patients may have been bedbound and/or may have been receiving mechanical ventilation while awaiting the transplant surgery. Immobility increases these patients’ risk for developing deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and subsequently developing PE. It is important to understand that lung transplant recipients are at increased risk of pulmonary infarction secondary to PE because the bronchial circulation is not reestablished during the transplant, and until collateral vessels form in a few weeks, these patients are relying on blood supply from the pulmonary circulation. If PE is suspected, CT of the chest with IV contrast material should be performed per the PE protocol.

The imaging findings of hemorrhage and PE are the same in lung transplant recipients as in nontransplant patients. Hemorrhage manifests as hyperattenuating fluid (higher attenuation than that of simple fluid) or a hyperattenuating mass (if it is a hematoma) that often has a heterogeneous appearance. PE manifests as hypoattenuating and well-defined filling defects in the contrast material–opacified pulmonary artery branches. These filling defects can be occlusive or nonocclusive; nonocclusive acute PE is centrally located in the vessel lumen, rather than eccentric. Patients with coagulopathy and patients who are receiving anticoagulation therapy for DVT or PE may have both hemorrhage and PE on imaging. Figure 6 shows a patient with bilateral chest-wall hematomas.

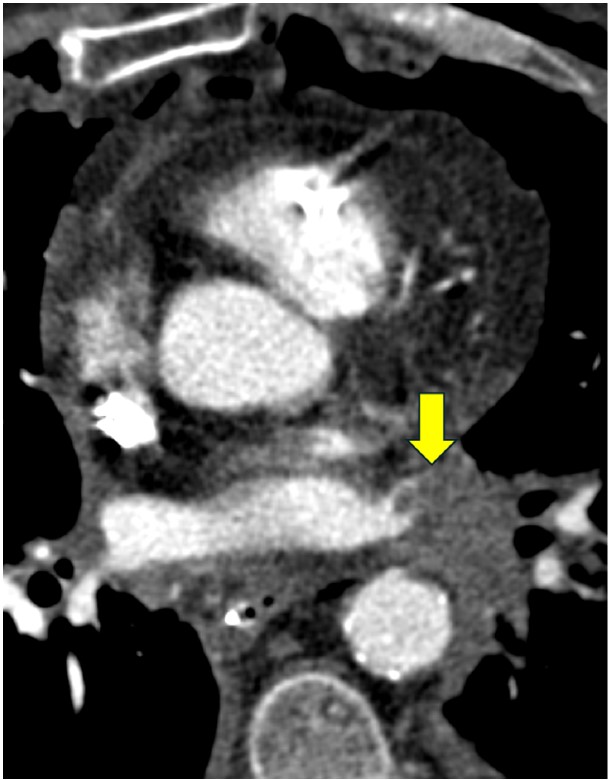

Pulmonary vein thrombosis and pulmonary venous anastomotic stenosis occur during the immediate and early postoperative periods, usually within 48 hours of lung transplant [8]. In pulmonary vein thrombosis, CT of the chest with IV contrast material shows a filling defect within a pulmonary vein, which may or may not be accompanied by consolidation, ground-glass opacities, and septal-line thickening in the lung parenchyma drained by the thrombosed pulmonary vein; the airspace opacities and septal-line thickening represent edema and hemorrhage due to venous ischemia and infarction. Endovascular intervention can be attempted, but cases of severe pulmonary vein thrombosis require surgery. Figure 7 (left) shows a patient with pulmonary vein thrombosis.

The pulmonary venous anastomosis is created adjacent to the left atrium. Stenosis of the pulmonary venous anastomosis is rare compared with stenosis of the pulmonary arterial anastomosis. On imaging, stenosis manifests as a focal narrowing of the pulmonary vein anastomosis that may or may not be accompanied by findings of venous ischemia and infarction in the lung parenchyma drained by the affected pulmonary vein, such as consolidation, ground-glass opacities, and septal-line thickening. As with pulmonary vein thrombosis, treatment options include endovascular intervention and, in severe cases, surgical repair. Figure 7 (right) shows a patient with pulmonary venous anastomotic stenosis.

Mechanical Complications

Mechanical complications include pulmonary torsion and lung herniation. Pulmonary torsion is a very rare complication of lung transplant and occurs during the immediate and early postoperative periods. A risk factor for lung torsion is when the donor lung is small relative to the recipient thoracic cavity, which means that the allograft is more mobile and likely to twist around its vascular pedicle after the transplant [9]. Careful size matching between the donor lung and the recipient chest cavity before the transplant surgery has greatly reduced the risk of lung torsion; however, given the potentially catastrophic consequences of torsion and the need for emergent surgical intervention, it remains an important diagnosis to be aware of. As previously stated, lung transplant recipients are particularly vulnerable to allograft ischemia and infarction because the bronchial circulation is not reestablished during transplant and the lung allograft must rely on pulmonary circulation until collaterals can form. Vascular compromise of the allograft due to torsion can result in severe allograft damage, allograft failure, or even death.

Imaging findings of pulmonary torsion can involve a lobe (in lobar torsion) or the entire lung (if the entire lung has twisted around its vascular pedicle). Pulmonary torsion can manifest as volume loss or collapse of the affected lobe or lung; it can also manifest as rapid expansion or opacification of the affected lobe or lung. Because of the twisting that occurs in torsion, patients with torsion have abnormal orientations and positions of anatomic structures such as lobes, hila, fissures, vessels, and airways. There may be abrupt cutoff of vessels and bronchi at the site of twisting. If pulmonary torsion is confirmed or suspected, the transplant physicians should be notified immediately to salvage as much of the allograft as possible. Pulmonary torsion requires emergent surgery to prevent allograft infarction and patient death.

Lung herniation can occur anytime after lung transplant. A major risk factor for lung herniation is increased intrathoracic pressure, as can be seen in patients with persistent cough due to pneumonia or aspiration after transplant. On imaging, herniated lung has an abnormal contour with a portion of lung bulging into the chest wall; this can occur at surgical sites (such as thoracotomy incisions) or at intercostal spaces. Mild herniation involving a small portion of the lung allograft with normal-appearing parenchyma is not worrisome. However, herniation involving a large portion of the allograft or deep herniation into the chest wall places the patient at risk for atelectasis, ischemia, infarction, and gangrene of the herniated lung, all of which can manifest as opacities within the herniated portion of lung. Surgical repair of the chest wall may be necessary in cases of pulmonary infarction or gangrene. Figure 8 shows a patient with lung herniation.

Conclusion

Lung transplant is increasingly becoming a cure for many patients with end-stage lung disease. In addition to academic chest radiologists, private practice radiologists and general radiologists are likely to encounter lung transplant recipients at some point in their careers. It is therefore essential for all radiologists to have a basic understanding of lung transplant complications—both common complications such as pneumonia and rare but life-threatening complications such as torsion. Although great progress has been made since the 1960s, the mean life expectancy of lung transplant recipients lags behind that of other organ recipients at only 6–7 years after transplant [10]. Early complications account for much of the morbidity and mortality in lung transplant recipients. These complications must be accurately detected and described when interpreting imaging studies, and they should be taken into account when protocoling imaging studies for lung transplant recipients. By doing so, radiologists can contribute to the postoperative care of lung transplant patients and can help optimize the quality and the duration of their posttransplant lives.

ERRATA: The winter issue featured this article with production errors, including inadvertent unauthorized changes to the title, introduction, and figures 3 and 4. We regret these errors and have republished the complete, corrected article for clarity.

References

- Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. National Data: Transplants in the U.S. by Region. optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data. Published 2024. Accessed August 25, 2024

- Kim SJ, Azour L, Hutchinson BD, et al. Imaging course of lung transplantation: from patient selection to postoperative complications. Radiographics 2021;41:1043-63

- Masson E, Stern M, Chabod J, et al. Hyperacute rejection after lung transplantation caused by undetected low-titer anti-HLA antibodies. J Heart Lung Transplant 2007;26:642-45

- Levine DJ, Hachem RR. Lung allograft rejection. Thorac Surg Clin 2022;32(2):221-29

- Shah RJ, Diamond JM. Primary graft dysfunction (PGD) following lung transplantation. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2018;39:148-54

- Snell GI, Yusen RD, Weill D, et al. Report of the ISHLT Working Group on Primary Lung Graft Dysfunction, part I: definition and grading – a 2016 consensus group statement of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017;36:1097-1103

- Adelmann D, Koch S, Menger J, et al. Risk factors for early bleeding complications after lung transplantation – a retrospective cohort study. Transpl Int 2019;32:1313-21

- Kim SJ, Short RG, Beal MA, et al. Imaging of lung transplantation. Clin Chest Med 2024;45:445-460

- Amadi CC, Galizia MS, Mortani Barbosa EJ Jr. Imaging evaluation of lung transplantation patients: a time and etiology-based approach to high-resolution computed tomography interpretation. J Thorac Imaging 2019;34:299-312

- Verleden GM, Glanville AR, Lease ED, et al. Chronic lung allograft dysfunction: definition, diagnostic criteria, and approaches to treatment – a consensus report from the pulmonary council of the ISHLT. J Heart Lung Transplant 2019;38:493-503