Deborah A. Baumgarten, MD, MPH

2025-2026 ARRS President

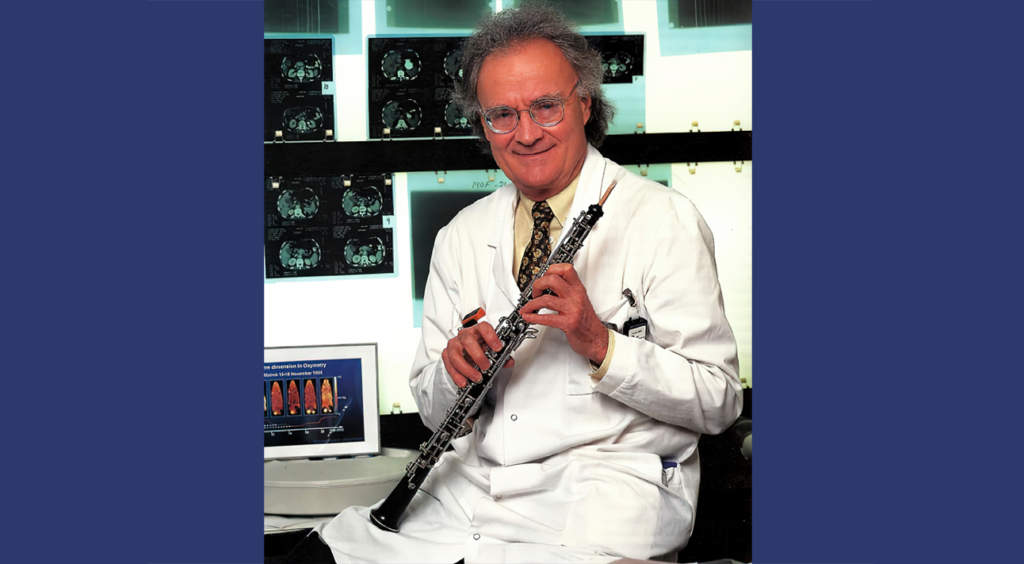

For our next installment of serendipity here in InPractice, we’re jumping ahead pretty far in time, as you’ll note by the color photograph of Professor Torsten Almén. As a young radiologist from Malmo, Sweden (not far from Copenhagen, Denmark), he was concerned about the pain of injected iodinated contrast, especially when it was administered arterially.

Dr. Almen’s serendipitous contribution is that he was struck by how little his eyes stung when swimming in the relatively isotonic Baltic Sea, as compared to the more hypertonic North Sea. He then wondered if a patient’s pain had anything to do with the tonicity of the contrast material that was administered. In 1967, Almen went to Temple University in Philadelphia, PA as a postdoctorate fellow and was given the choice on working on a steerable catheter that he’d helped design or working on this notion of toxicity and tonicity of contrast. Fortunately, he chose the latter. Almen was able to show in a bat model that his theory was correct, but he had to go about designing something that could be utilized in humans—a more ideal contrast agent. He wasn’t a chemist, so he bought some textbooks, taught himself the basics of organic chemistry, and tried to get someone interested in producing this theoretical compound. He finally persuaded Nygard, which later became Nycomed, to produce his low osmolar contrast material metrizamide in 1969. It was released several years later, quickly followed by other contributions to low osmolar contrast: Isovue by Bracco in 1981, Omnipaque by GE in 1982, and Optiray by Mallinckrodt in 1989.

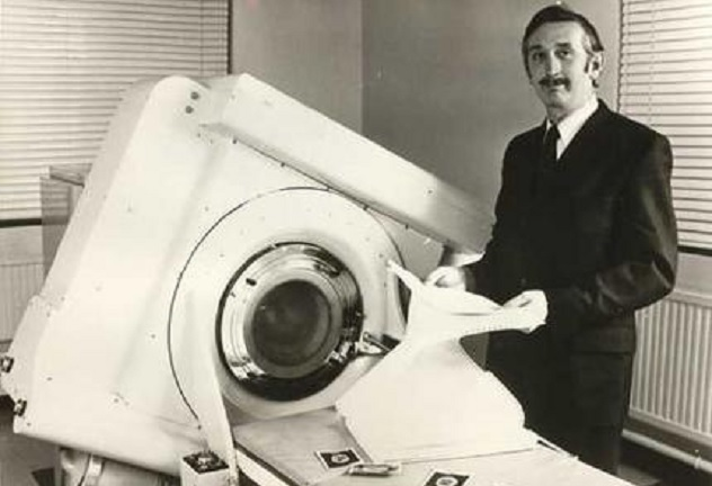

I dare say this gentleman is at least as recognizable as our society’s namesake, Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen. Sir Godfrey Newbold Hounsfield has had such a profound effect on our field. It was during an outing in the country when the idea came that he could determine what was inside a box by taking x-rays from all angles around the object, then somehow combine the different shadows the x-rays would produce to form an image of that object.

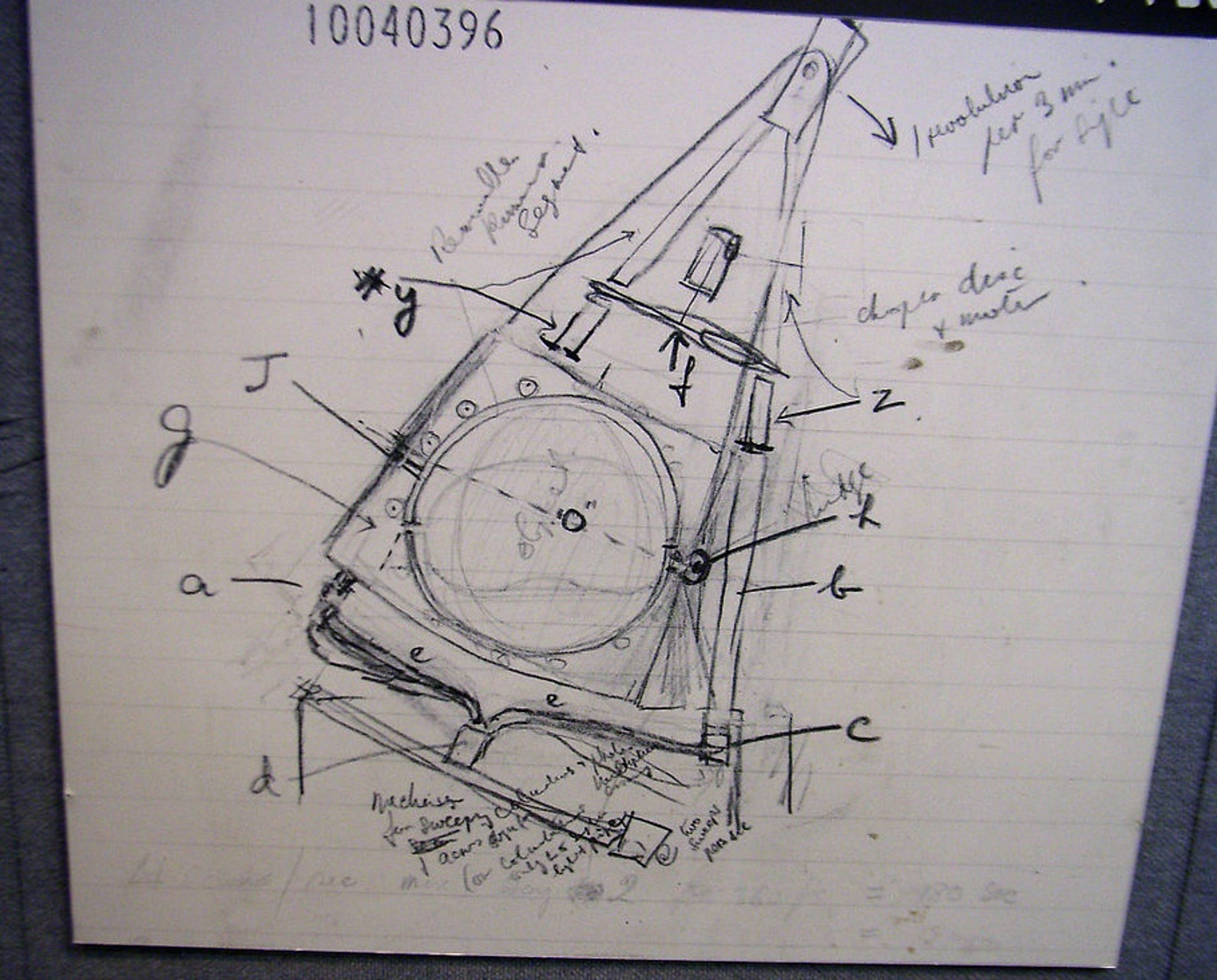

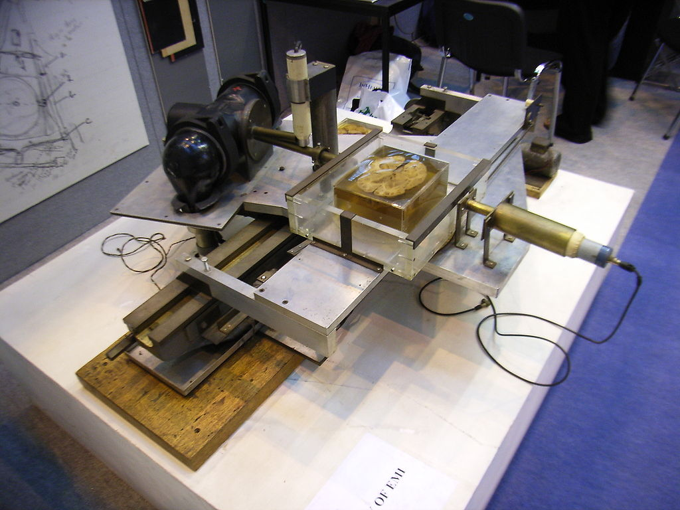

This is a sketch of his first idea of the CT scanner and the prototype. It’s one thing to formulate the idea of using x-ray readings, of course. But it was Dr. Hounsfield’s open mind that allowed him to realize not only the potential, but the necessity of using computers to analyze the data generated by taking all of the x-ray angles needed to create a CT image.

. . . compared to his prototype!

The following quotation by Dr. Louis Pasteur is particularly appropriate in this particular case: “In the field of observation, chance favors only the prepared mind.” Doctors Allan Cormack and Hounsfield shared the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work in CT.

Moving away from radiological discoveries for a moment, I love this quotation: “Eureka, I found what I wasn’t looking for!” This is associated with a book called Happy Accidents by a renowned abdominal radiologist named Dr. Mort Meyers, who spent his career at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. Again, emphasizing that the open mind is primed to take advantage of serendipity, how many of you know that the invention of the microwave oven had its origins when an engineer working with radar sets had a candy bar melt in his pocket, realizing it must’ve been from emitted radio waves? Or that Viagra was discovered by Pfizer when looking for a drug that increased blood flow to the heart, only to find that it increased blood flow a little lower? Or the discovery of artificial sweeteners by Constantin Fahlberg, a chemist working on coal tar derivatives, came from his inadvertent tasting of saccharine? Aspartame’s discovery came later, thanks to James Shaler, a chemist working on anti-ulcer drugs. Sure, their tasting of unfamiliar lab compounds is completely not up to today’s standards, but we can excuse them for that.

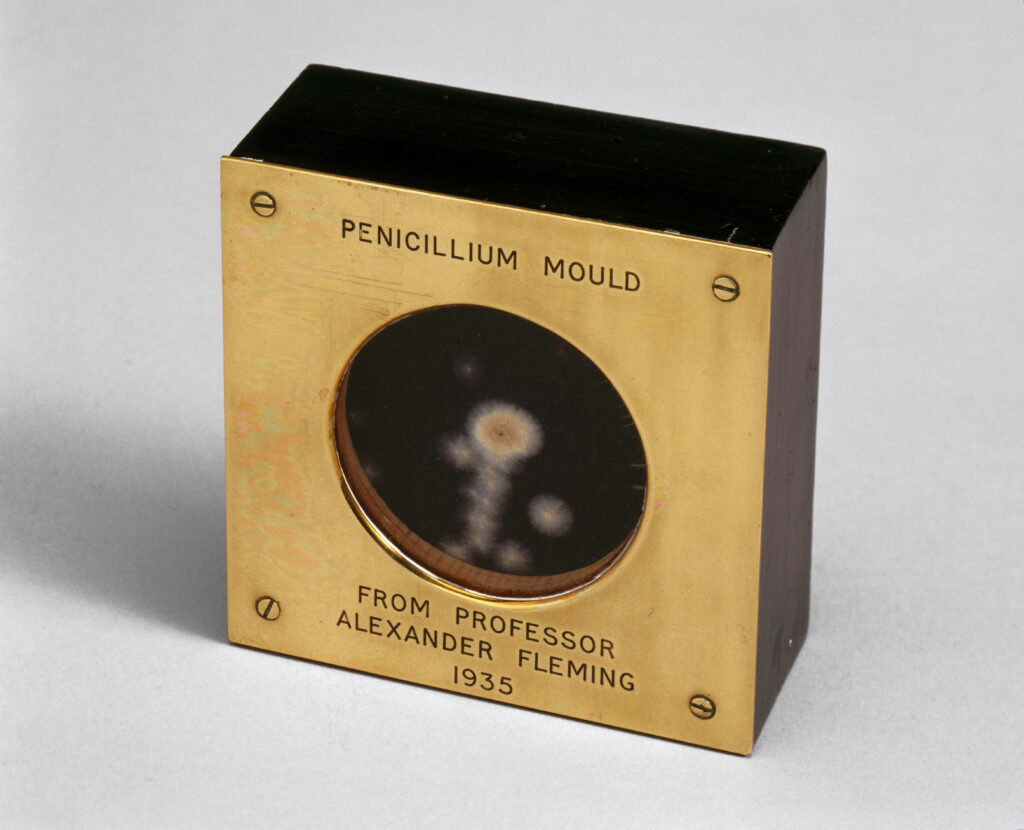

There are so many more examples of serendipity in science. Sir Alexander Fleming‘s discovery of penicillin came while working on compounds to inhibit bacterial growth, serendipitously noting one plate that had some mold on it seemed to be doing better than the other ones. Or veterinary pathologist Frank Schofield‘s discovery that spoiled sweet clover hay led to a hemorrhagic illness in cows, eventually leading to the isolation of dicoumarol, or Warfarin. Or the serendipity of the population in the United Kingdom erroneously getting a half-dose of the Oxford AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine before a second full dose that gave a 90% effectiveness rate against COVID-19, as compared to the 62% when two full doses were tested in Brazil and South Africa.

British biologist and pharmacologist Dr. Alexander Fleming gave this sample of penicillium notatum to a colleague at St. Mary’s Hospital, London, in 1935.

Physiologist Menko Victor “Pek” van Andel at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands studies serendipity patterns in knowledge and discovery, and he’s categorized three main types of serendipity. Positive serendipity is when a surprising fact is seen and followed by a correct interpretation (e.g., x-rays). Pseudo-serendipity is to discover something you were looking for, but in a surprising way. An example that van Andel uses is penicillin. Meanwhile, negative serendipity is when a surprising fact is seen, but not optimally investigated. And I’d like to think Dr. Donald Cameron never pursuing sodium iodine salts would be that kind of negative serendipity, although it was found positively later by Dr. Earl Osbourne (see Part I here).

Pek van Andel was one of the first researchers to extract serendipity patterns for accidental unsought knowledge discovery.

Others have built on van Andel’s work, including Darbellay et al., who published a paper titled “Interdisciplinary Research Boosted by Serendipity.” Their contention is that getting rid of the silos that house most of our disciplines and opening one’s mind to the unexpected are fundamental to the work of researchers who position themselves between and beyond disciplines. That serendipity itself is an important part of interdisciplinary research. As a creative process, serendipity is foundational in interdisciplinary collaboration, boosting the exchange of ideas to exploit the unexpected.

Examples of this interdisciplinary research aided by serendipity mentioned by Darbellay and colleagues include a team at Dow Chemical tasked with inventing a chemical compound for protecting the windscreens of airplanes. Upon application of substance 401, the researchers realized they could no longer remove the measurement device that they were utilizing on the windscreen. The team was worried because this was very costly equipment, so they called their boss, Harry Coover, who had a doctorate in chemistry. When faced with this unexpected effect of the substance 401, he realized the researchers had unknowingly and unintentionally discovered superglue, which was a substance that could bond metal and glass. Under Coover’s initiative, Dow abandoned trying to find something better for windscreens, channeled its efforts into developing superglue, and began marketing the product so many of us use today. Other accounts dispute Darbellay et al.’s retelling of this discovery, instead noting that Coover discovered superglue (cyanoacrylate) at the Eastman Kodak company, where he realized clear plastic gun sights stuck to everything. He first rejected the substance but later recognized its potential as an adhesive, so serendipitous no matter the origin!

Ironically, the near complete opposite of superglue was also a serendipitous discovery. Spencer Silver and colleague Arthur Fry stumbled upon the idea for Post-it® notes while working at 3M. Silver discovered an adhesive that sticks permanently without a permanent bond and only does so in one direction, allowing an object to be repositioned. Fry’s contribution was finding use for the adhesive while singing in his church choir and lamenting that his bookmarks kept falling out of hymnals—his own eureka moment when he remembered Silver’s invention. The original yellow? Also, an accident; it was the color of a scrap of paper in an adjoining lab.

Art Fry, 93, in Saint Paul, Minnesota

Switching gears for just a moment, how about looking at serendipity on a more personal level? I’ve always been fascinated by the role of luck in my life and in the lives of others. When I was a child, whenever anything good in my life happened, I would tell my mom “I got lucky,” to which my mom would say, “we make our own luck.” This phrase has stuck with me for a very long time, and may be my own definition of serendipity: being open to possibilities when they happen and taking advantage of them. In one sense, I could describe my ascent to becoming president of the American Roentgen Ray Society as luck. Again, lucky in the sense that I repeatedly said “yes” to volunteer opportunities, even if that opportunity wasn’t glamorous or meant a lot of work.

So, here is what I conclude about serendipity. For those of you already well involved in research, getting your feet wet in research, or wanting to become involved in research, know that chance, luck, serendipity—whatever you want to call it—will play a role in your career. Keep an open mind, expect the unexpected, then turn it on its head. Seek out ways to collaborate with people who are in unrelated fields. Take advantage of the opportunity to network and build your community at meetings such as ARRS with those outside of your chosen field or discipline and those inside your chosen field or discipline. There will be so many more serendipitous discoveries in our lifetime and many lifetimes to come. It’s what keeps our field and so many others so very interesting. I understand everybody’s time is limited and valuable, but truly consider an opportunity before saying “no.” You never know which opportunities will lead to something bigger, so keep an open mind about saying, “yes.” You never know who will be touched by your words and actions, who will change your life with a chance encounter, or whose lives will be changed by a chance encounter with you.

References:

- Nyman U, Ekberg O, Aspelin P. Torsten Almén (1931-2016): the father of non-ionic iodine contrast media. Acta Radiol 2016. 57:1072–1078

- Gagnon L. ‘A diagnostic revolutionary’—the legacy of Godfrey Hounsfield. Aunt Minnie website. www.auntminnie.com/clinical-news/ct/article/15631616/a-diagnostic-revolutionary-the-legacy-of-godfrey-hounsfield. Published August 11, 2022. Accessed August 8, 2025

- Meyers MA. Happy accidents—serendipity in modern medical breakthroughs. New York: Arcade Publishing 2007

- Van Andel P. Anatomy of the un-sought finding. Brit J Philo Sci 2014. 45;631–648

- Darbellay F, Moody Z, Sedooka A, Steffen G. Interdisciplinary research boosted by serendipity. Create Research J 2014. 26;1–10

- Post-it® website. www.post-it.com/3M/en_US/post-it/contact-us/about-us. Accessed August 8, 2025