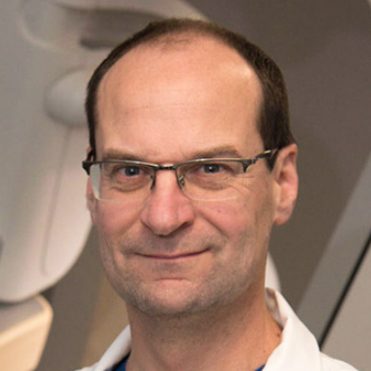

Jonathan Kruskal

2021–2022 ARRS President

Those of you I have connected with virtually over the past year may recall that, in addition to family photos, my office (and thus my zoom background) is adorned with my old cricket bat, indigenous South African art, Khoisan necklaces, hummingbird photographs, and Shona stone sculptures. These are just a few artefacts that represent my cultural identity, on which I’ve been reflecting a lot these days.

One of the reasons I emigrated from South Africa after completing my medical and basic science training was to escape the abhorrent system of apartheid that I witnessed up close from a young age. My wife and I touched down in the U.S. in 1987 filled with hope and much anticipation. The days of watching fellow human beings suffer at the hands of systemic racism, marginalization, violence, and oppression were behind us, or so we thought. Perhaps our departure was one way of social distancing from that awful pandemic, though much guilt persists knowing that “running away” would not contribute to a solution in any lasting or meaningful way.

Demolishing Normalcy

Fast forward to the year 2020, and we find ourselves grappling with the factors that contributed to George Floyd’s death. Along with the outbreak of COVID-19, more than 15 long months ago, and the ubiquitous opioid addiction crisis, the America that we chose to move to is experiencing more than a single pervasive pandemic and finds itself in desperate and urgent need of a reckoning with structural racism.

The last year has exposed centuries-long inequities, disparities, and ignorance, which impact our employees, peers, patients, loved ones, and communities in ways big and small, seen and unseen, told and untold. Absent diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) strategies, combined with social distancing protocols, full-time remote work, technology and commitment overload, and skyrocketing mental health concerns have rightfully demolished what we once believed were the tenets of effective teams; the trademarks of normalcy. To return to what we as radiologists do best—providing top-quality, safe, timely, and evidence-based care—we must work together to dismantle, then to rebuild the status quo. How can we do this?

We Must Row as One

Whether based in a hospital, private practice, or academia, we need to develop and implement DEI strategies that will build high-performing teams through intentional inclusion practices. It’s the only way we can ensure the highest-quality care for our patients, eliminate care and outcome injustices, and begin to narrow the health disparity gaps. We must acknowledge that, yes, we all have biases, many of which are unconscious.

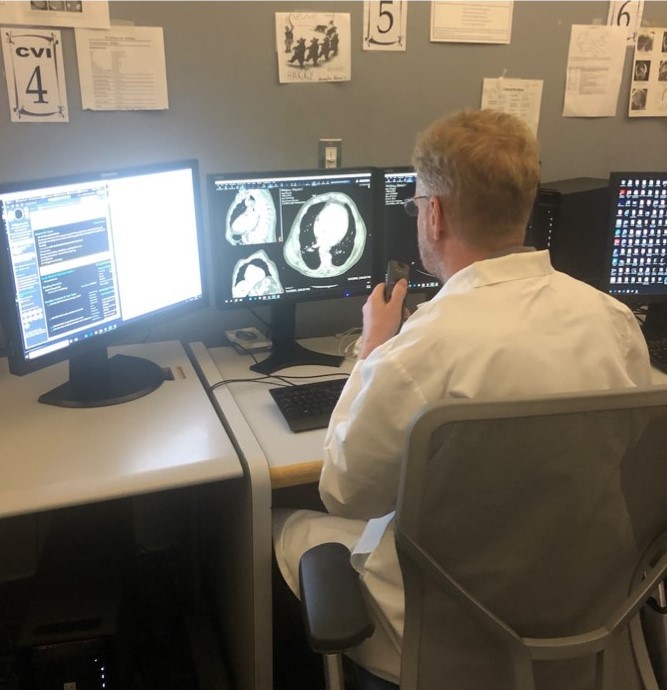

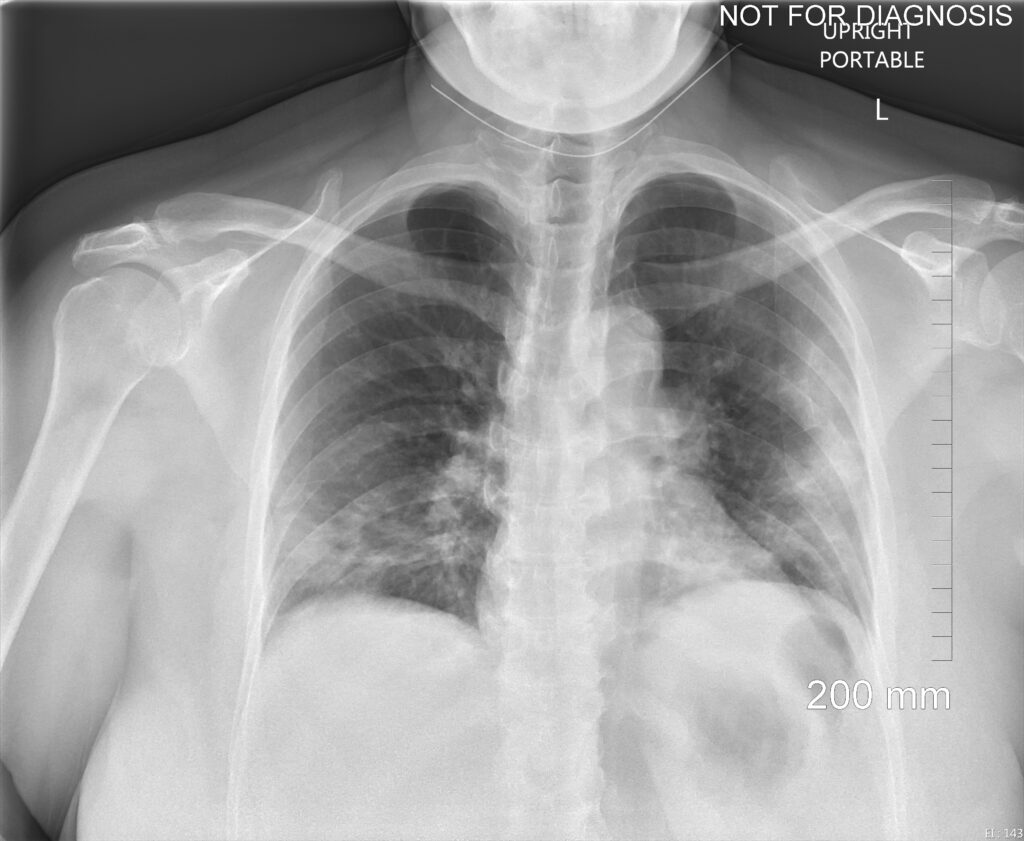

Consider the myriad of players and moving parts in our ecosystems: our technologists acquiring and managing images; our IT colleagues facilitating image interpretation, data management, and report communication; and our nurses providing compassionate, patient-centered care during minimally invasive procedures. We also have the essential contributions of our translators, transporters, schedulers, nurse navigators, medical assistants, advanced practice providers, administrators, and image repository staff. To effectively serve our patients, we must understand, respect, trust, and listen to one another. Simply put, we must row as one.

Doing the Work

As a first step, I encourage you to take Harvard University’s Implicit Aptitude Test to better understand some of your own biases. Set aside uninterrupted time, and take the test with an open and honest mind. You can also ask your employees or colleagues to do the same. Take time to discuss what everyone learned, and listen to each participant. Sit with them, either in person or virtually, and truly hear their experiences and perspectives. Make sure to create an environment of safety, compassion, and open-mindedness for each gathering. You can also consider designing a DEI survey for your team to receive anonymous or attributed feedback. In the spring of 2019, Harvard University created a three-minute “pulse survey” for its community. The executive summary, final report, and data charts and tables are available here.

In these discussions and surveys, you can also delve deeper into topics such as cultural humility, microaggressions, and the difference between bystanders and “upstanders.” The emerging practice of cultural humility, a commitment to lifelong learning about global cultural differences, encourages us to inquire and learn about the experiences and identities of others. Ignorance can lead to an intended or unintended microaggression, which Medical News Today defines as “a comment or action that negatively targets a marginalized group of people.” Another important term to learn and practice is upstanders, or people who speak or act in support of an individual or cause, particularly on behalf of a person being attacked or bullied.

The Concept of Ubuntu

The Zulu and Xhosa concept of Ubuntu emphasizes the importance of “being oneself through others,” a form of humanism best expressed by the phrase, “I am because of who we all are.” Imagine if we realized that our best personal function was dependent on the function of our entire team?

To sustain and elevate team functionality, we must adopt this philosophy in a way that resonates with you. Perhaps it’s by remembering the Golden Rule, which instructs us to treat others the way we would like to be treated ourselves. Maybe it’s by thinking about Aristotle’s historic quote: “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”

At the core of our impact as imagers is a broad swath of races, cultures, ideologies, genders, religions, age groups, and much more. Over the next year, we will continue to share DEI resources and invite members of our ARRS family to volunteer, as we develop educational materials that are the building blocks for individual members and practices to rebuild their teams. To submit ideas and feedback, please email me directly at jkruskal@bidmc.harvard.edu.