David W. Townsend

Professor of Radiology (Retired), National University of Singapore

Director (2010–2018), Singapore Clinical Imaging Research Center

Dr. Townsend receives royalties from Siemens for the co-invention of the PET/CT and receives no compensation from Lucerno Dynamics as a voluntary scientific adviser.

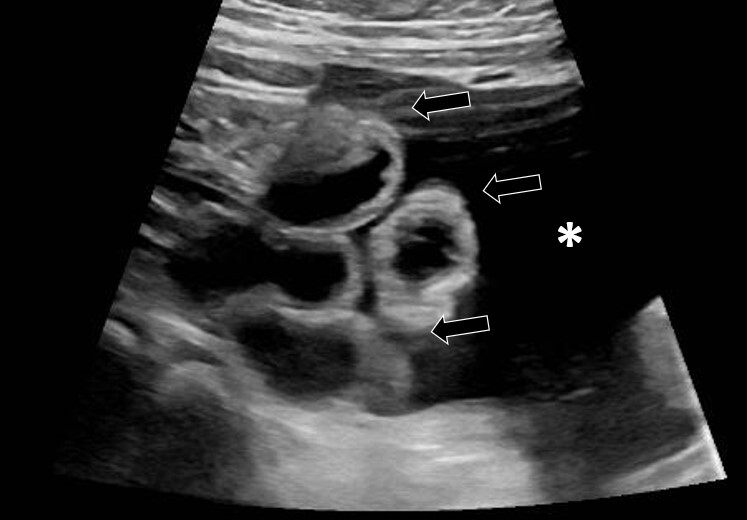

When performing an imaging study involving the injection of a radioactive compound into a patient, it is implicitly assumed that the compound is injected directly into the circulation, without any infiltration or extravasation into the tissue surrounding the injection site. Failure to achieve this goal will have a number of unintended consequences, depending upon the extent of the extravasation. Unfortunately, until recently, such extravasations have not been monitored, and in the cases where they occurred, the magnitude and extent were unknown.

Recently, I authored an article highlighting that such radiopharmaceutical misadministration resulting in extravasation is exempt from medical event reporting, owing to an outdated 1980 internal policy of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). This exemption applies even when the radiation dose to tissue locally exceeds the NRC threshold for event reporting. The policy was based on the assumptions that extravasations are a “frequent occurrence” and are “virtually impossible to avoid”; assumptions that are no longer valid today.

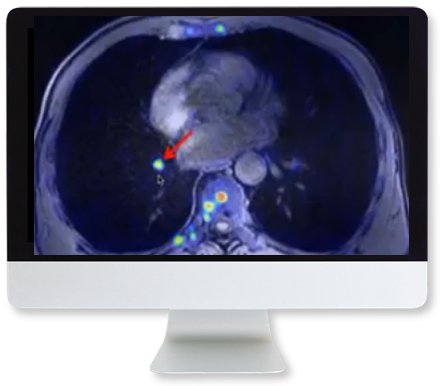

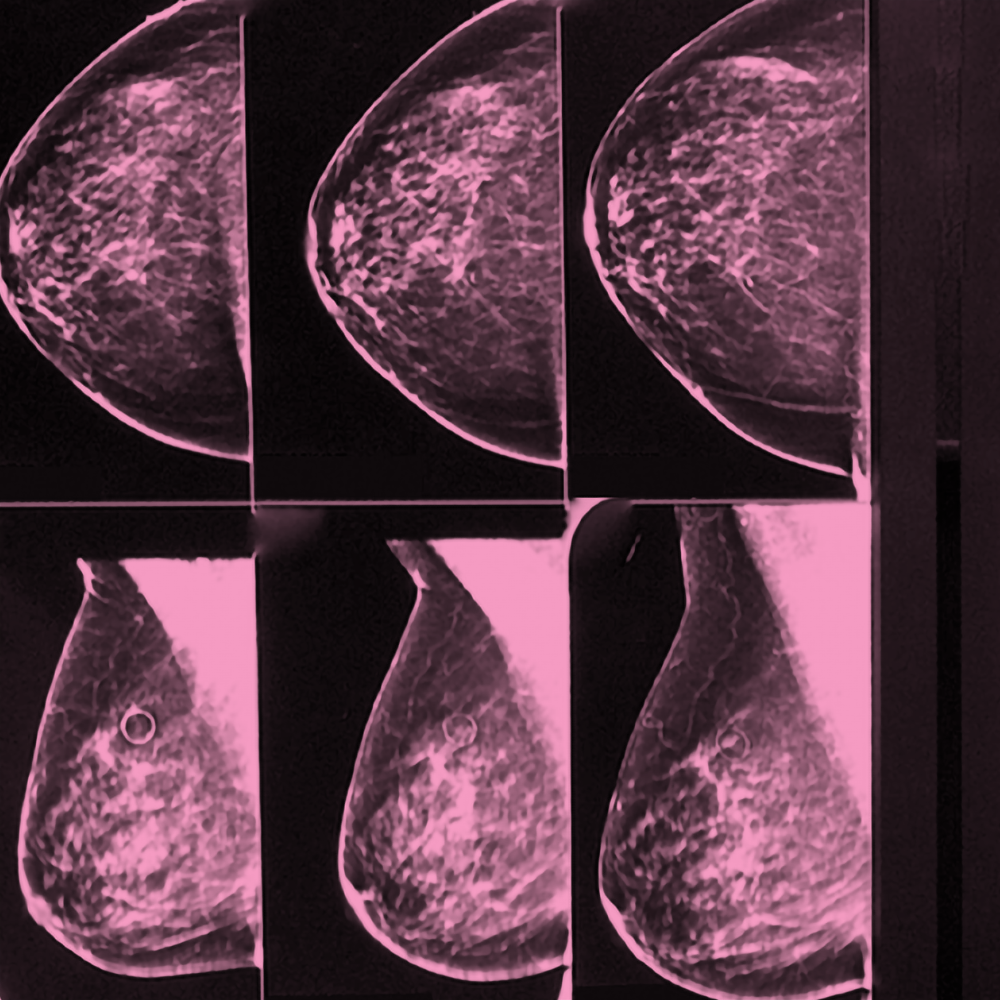

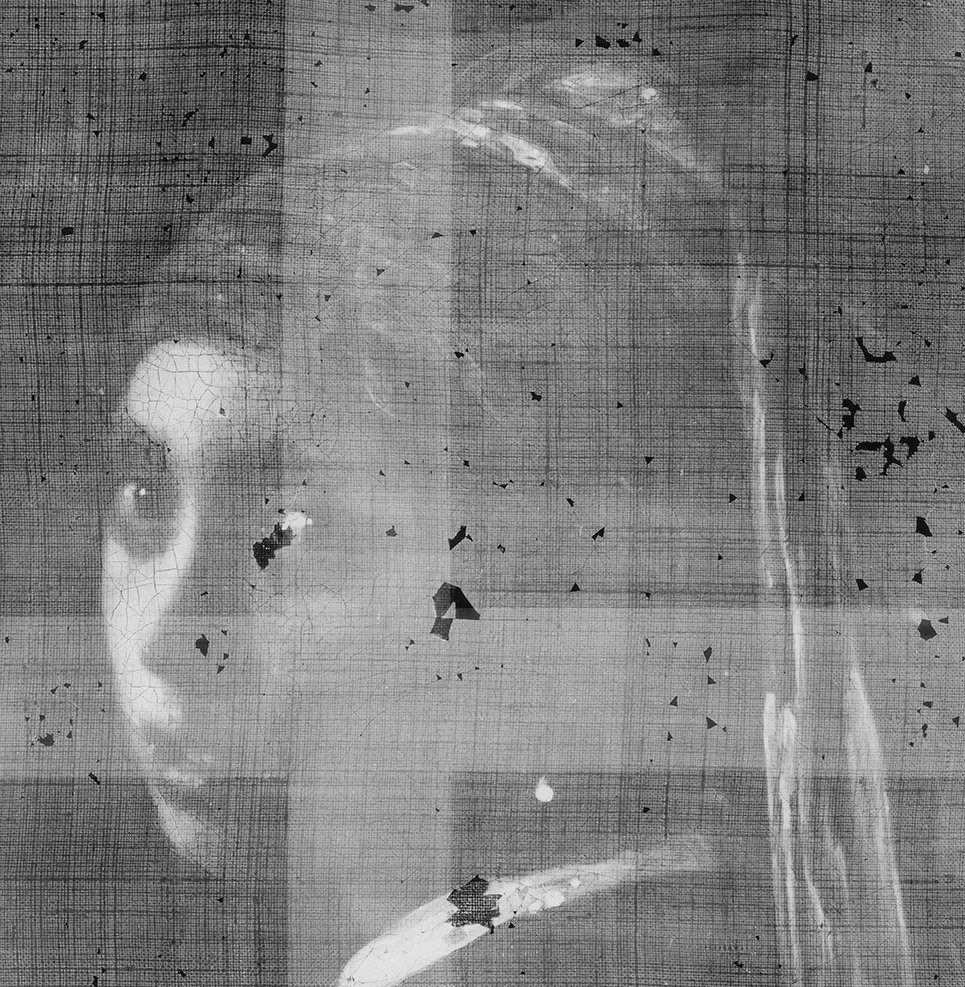

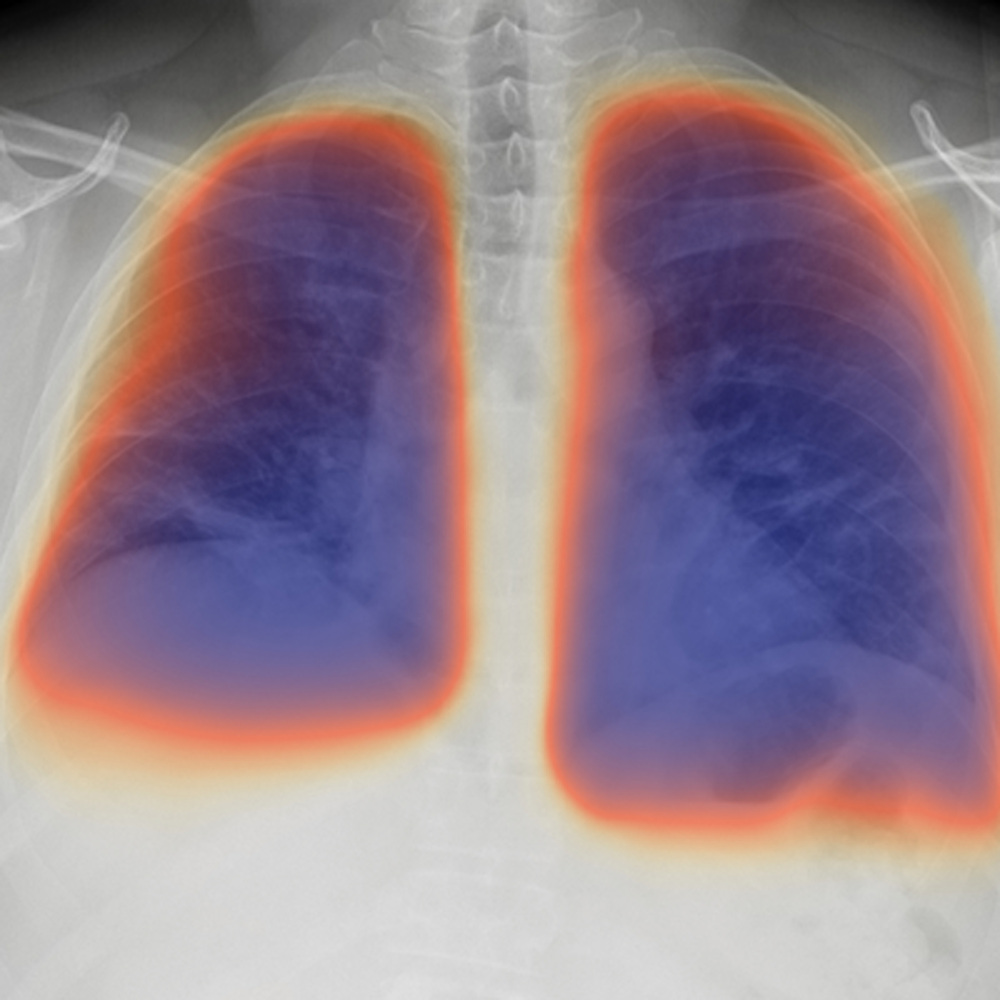

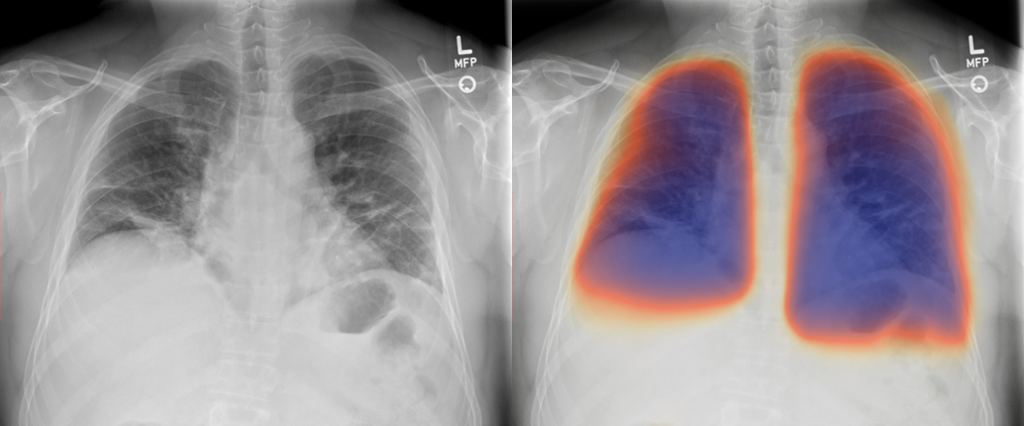

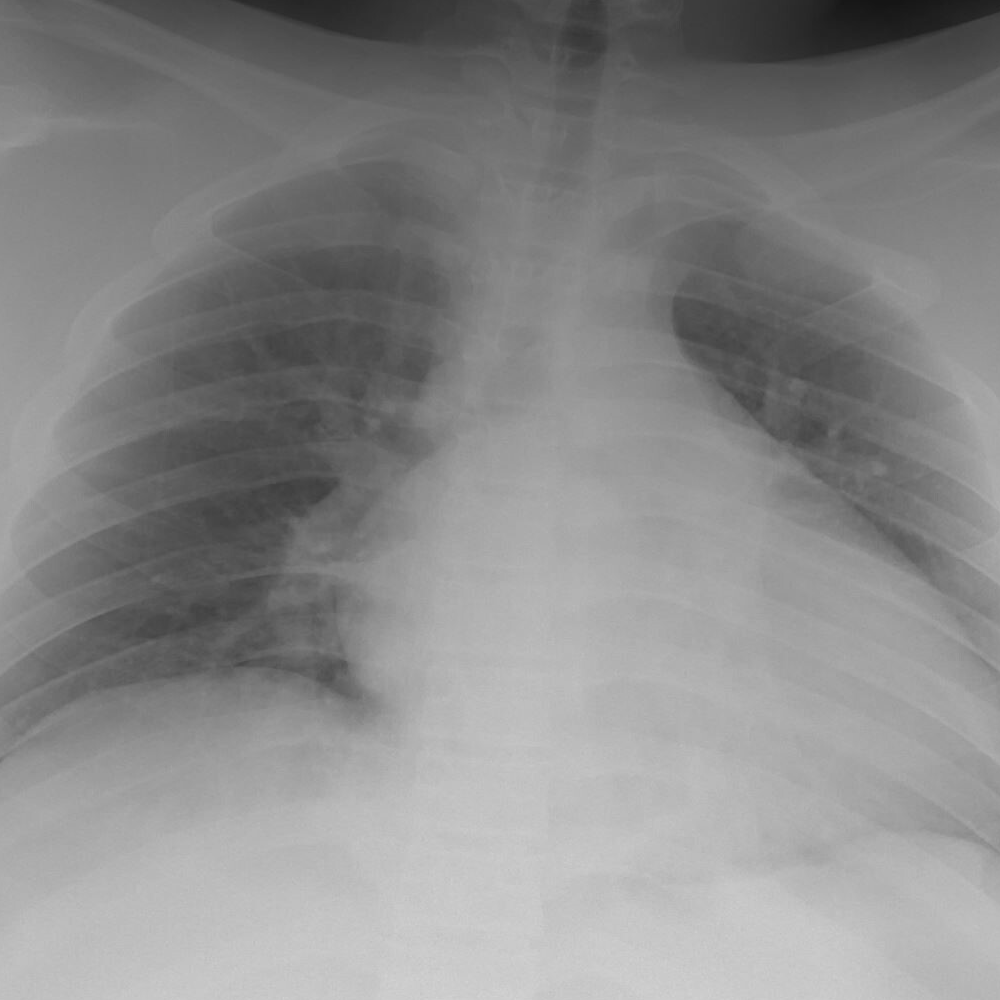

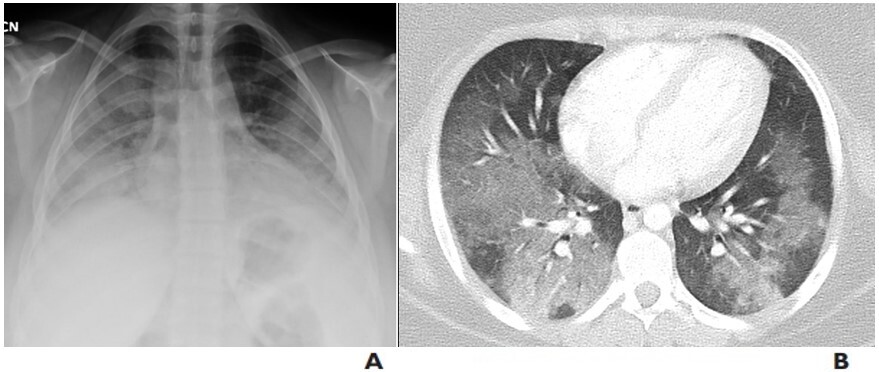

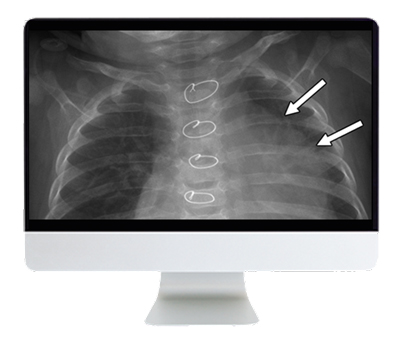

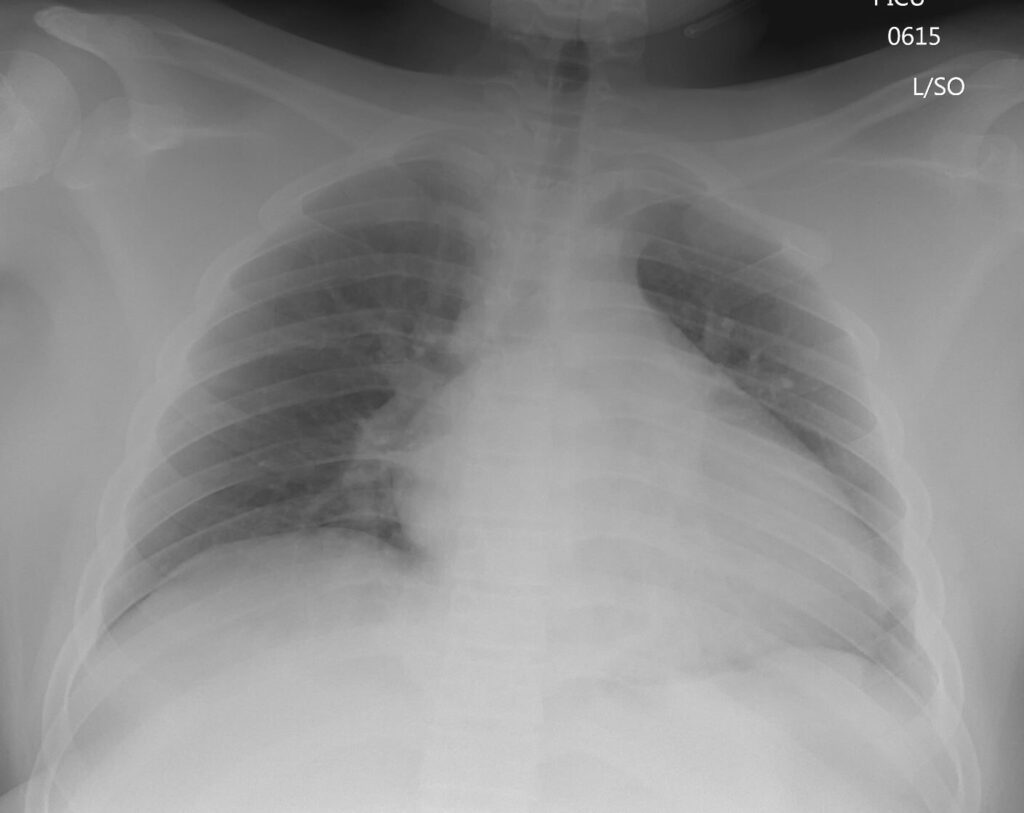

Since much of my career has been spent developing instrumentation and reconstruction algorithms for PET imaging, let us consider the imaging consequences resulting from the extravasation of an injection of a PET radiopharmaceutical. Obviously, its significance will depend upon the extent of the extravasation: the fraction of the radioactivity that remains locally at the injection site compared with that entering the circulation. Since the interpretation of the PET image assumes that all the radiopharmaceutical entered the circulation at the moment of injection, extravasation may affect the image both qualitatively and quantitatively. The reduced volume of radiotracer in the circulation may increase image noise that then obscures small, low uptake pathologies resulting in misinterpretation. Further, the uptake in a volume of tissue, such as a tumor, is estimated relative to the injected dose per unit weight of the patient, so that if the true dose injected is incorrect due to extravasation, the estimate of uptake in the tumor is also incorrect. This, again, potentially leads to misinterpretation of the study, particularly when it is used to assess response to a specific therapy.

In addition to these well-known effects on the image quality, there can also be a significant change in the dose distribution of the injected radiopharmaceutical. The majority of imaging studies meet the criteria of low, or very low, radiation dose to the patient. This assumes that the injection is directly into the vein and the radioactivity distributes uniformly throughout the body. Obviously, depending on the radiotracer, uptake in certain organs may be higher than others, but overall, a typical equivalent dose to tissue at the injection site is less than 1 mSv. Extravasation of the injection will change this distribution, resulting in potentially much higher doses at the site of the injection. In a study of 36 significant extravasations of injections for diagnostic imaging, all of them exceeded the NRC medical event reporting threshold of 0.5 Sv, and 80% of them also exceeded the 1-Sv limit that the nuclear medicine community takes as the threshold for an adverse tissue reaction. The dosimetry estimates in this study are based upon patient-specific biological clearance that assesses the dose in a 5-mL sample of tissue. However, as mentioned previously, the outdated 1980 NRC policy does not require such extravasations to be reported as a medical event, even when there is the possibility of tissue damage to the patient.

Within the context of radiation protection, such a contradictory approach makes little sense: a 1-Sv radiation dose externally resulting from radioactivity spilled on the patient is reportable, whereas a 1-Sv dose internally resulting from extravasation of an injection is not reportable. Obviously, a critical consideration is how often do such extravasations arise during the normal practice of nuclear medicine, and is it a significant problem? Almost 20 million nuclear medicine studies are performed in the US each year, and therefore, even a small percentage of extravasated injections represents a large number of patients. However, most centers do not monitor the quality of the injection, and therefore, their extravasation rate is unknown. Twelve centers have published eight studies of 3,254 patients acquired between 2003 and 2017 and identified an average rate of 15.5%

Bains A, Botkin C, Oliver D, Nguyen N, Osman M. Contamination in 18F-FDG PET/CT: an initial experience. J Nucl Med 2009; 50:2222

Krumrey S, Frye R, Tran I, Yost P, Nguyen N, Osman M. FDG manual injection verses infusion system: a comparison of dose precision and extravasation. J Nucl Med 2009; 50:2031

Osman MM, Muzaffar R, Altinyay ME, Teymouri C FDG dose extravasations in PET/CT: frequency and impact on SUV measurements. Front Oncol 2011; 1:41

Silva-Rodriguez J, Aguiar P, Sánchez M, et al. Correction for FDG PET dose extravasations: Monte Carlo validation and quantitative evaluation of patient studies. Med Phys 2014; 41:052502

Muzaffar R, Frye SA, McMunn A, Ryan K, Lattanze R, Osman MM. Novel method to detect and characterize (18)F-FDG infiltration at the injection site: a single-institution experience. J Nucl Med Technol 2017; 45:267–271

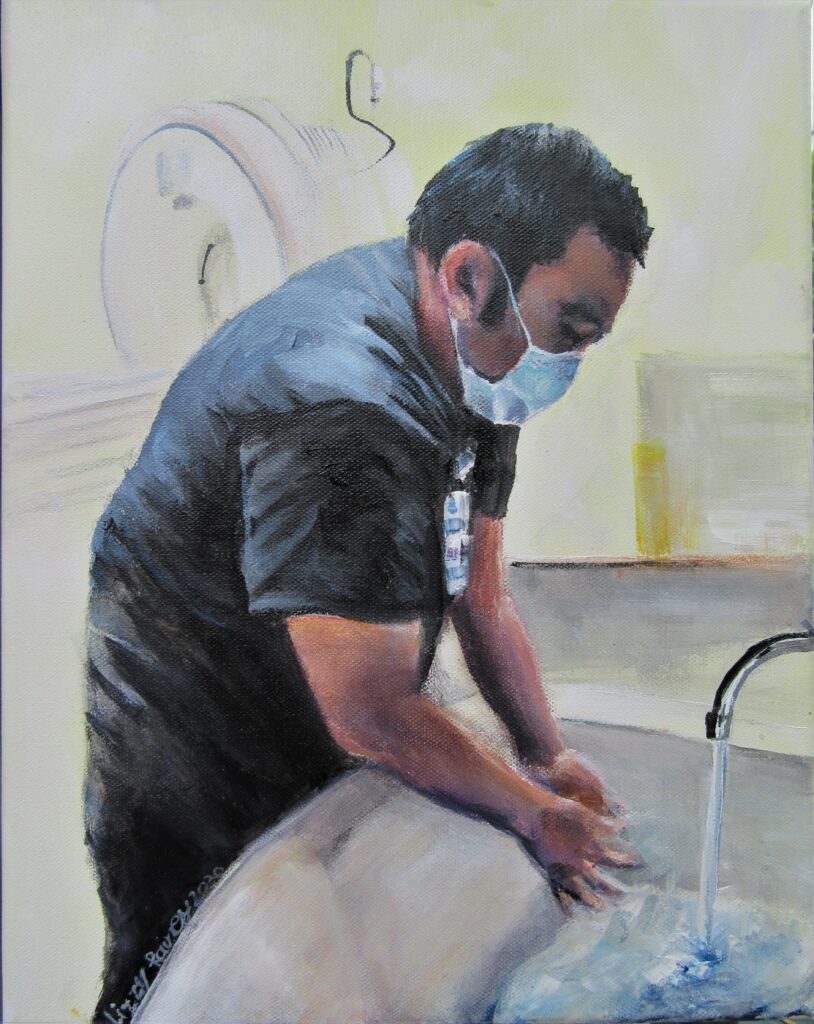

Such statistics invalidate the assumptions upon which the 1980 NRC policy was based: that extravasations are frequent and impossible to avoid. An average rate of 15% implies many centers have extremely low rates, and some centers have higher rates. The fact that there is a wide disparity of rates suggests that they are not impossible to avoid—some centers avoid them almost entirely. The studies in which I have been involved identified factors such as the tools used for the injection, the technique, and the experience of the technologist that influence the probability of extravasation, rather than any patient-specific factor. Consequently, with better tools, improved technique, and more experience, extravasation rates can be reduced to very low levels. We also showed that such improvements are sustained, and the rates do not increase again over time. If all centers monitored their extravasation rates and implemented an appropriate training program, such rates could be kept extremely low.

Based on these considerations, it is time for the NRC to update their 1980 policy to be consistent with all patient radiation exposure exceeding 0.5 Sv as reportable, whether external or internal. Such a change would be in the interests of patient safety and would encourage centers to monitor their extravasation rates and maintain them at very low levels. In addition, the quality of the imaging study would be improved, both from a qualitative and quantitative perspective. By reducing rates to very low levels, any increased administrative demand on the center to report extravasations would be kept to a minimum.

The NRC is considering a petition to update their 1980 policy, for which they are currently accepting public comment. As stated above, such a change would protect patient safety and improve the quality of imaging studies. Although the petition would require reporting of significant extravasations where the estimated tissue dose exceeds the 0.5-Sv threshold, it also suggests a 12-month regulatory reporting grace period to allow all centers to monitor and improve their injection techniques. It has been shown that even levels of 15% or above can be reduced (and maintained) at less than 1% with appropriate effort. Consequently, supporting this petition for change will introduce consistency into the NRC policy for radiation exposure, and it will further encourage centers to resolve an issue that compromises both patient safety and the diagnostic quality of the imaging study.

As a final point, it should be noted that all the above considerations apply even more so to therapeutics involving injected radioactive compounds, where an extravasated dose may have profound consequences for the patient.