Published January 21, 2022

Stephen E. Russek

Project Leader, Imaging Physics; Applied Physics Division

Codirector, MRI Biomarker Measurement Service

National Institute of Standards and Technology, US Department of Commerce

Karl F. Stupic

Director, MRI Biomarker Measurement Service

National Institute of Standards and Technology, US Department of Commerce

Kathryn E. Keenan

Project Leader, Quantitative MRI; Applied Physics Division

National Institute of Standards and Technology, US Department of Commerce

Medical imaging is rapidly advancing and includes many modalities: ultrasound (US), MRI, radiography, CT, PET, SPECT, and optical coherence tomography. New modalities, such as digital breast tomography and low-field MRI, are being integrated into the clinical workflow. Multimodal imaging, such as PET/CT and PET/MRI, and combined imaging therapy, such as MR linear accelerator, are rapidly expanding. Additionally, the amount of data extracted by radiologists by eye, via complex analysis tools, and using AI-based systems is dramatically increasing. Radiologists require that data are accurate and reproducible. To ensure this, calibrations and standards are needed. Phantoms—imaging calibration structures—are used to ensure scanner accuracy, stability, and comparability. Phantoms need to be readily available, easy to use, and have accurate and traceable components. In addition, imaging and analysis protocols must be rigorously validated, and the fundamental measurands, image-based biomarkers, must be carefully and precisely defined.

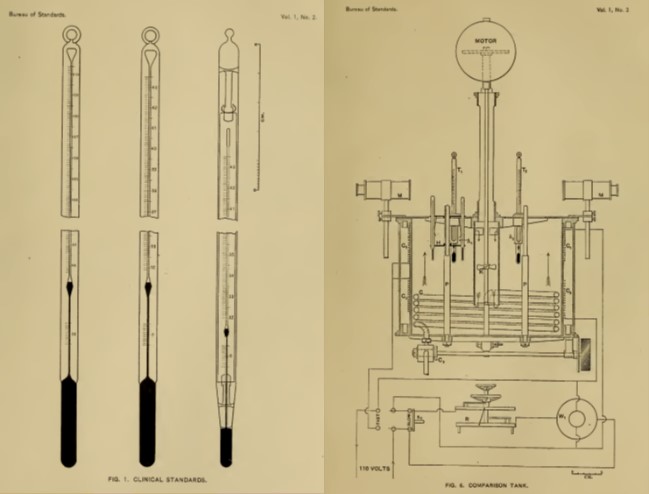

Many organizations have programs to assist in making image-based data more precise and reliable, including the Radiological Society of North America Quantitive Image Biomarker Alliance, National Cancer Institute Quantitative Imaging Network, American College of Radiology (ACR), National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Equipment Manufacturers Association, American Association of Physicists in Medicine, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM), National Physical Laboratory (United Kingdom), Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (Germany), and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). NIST, the US national metrology institute, has been assisting clinical, research, and medical device organizations in the development and dissemination of medical standards for over 100 years. An early example from around 1905 (Fig. 1) depicts calibration equipment and commercial medical mercury thermometers.

In the early 1900s, getting a universally accepted temperature scale was a critical issue. The need for medical metrology and standards has grown since then, and it is a critical part of our health care infrastructure. Below, we look at some recent NIST activities in standards for quantitative MRI.

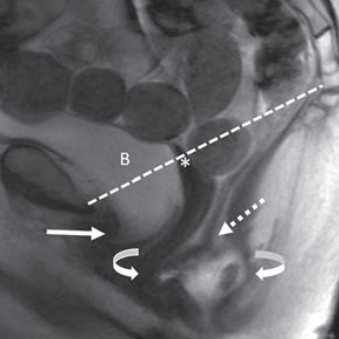

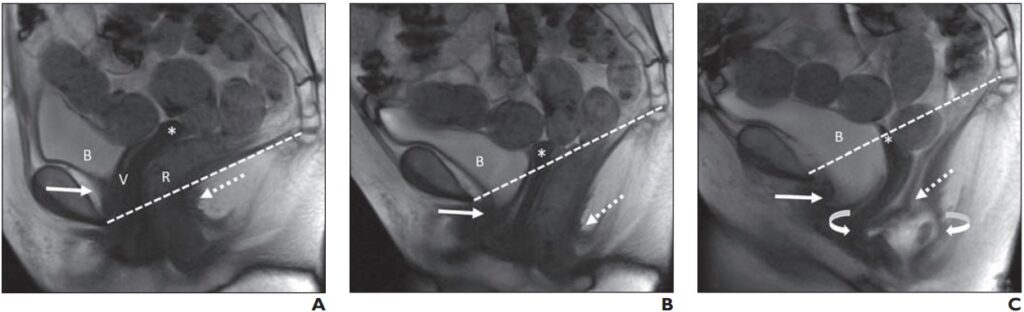

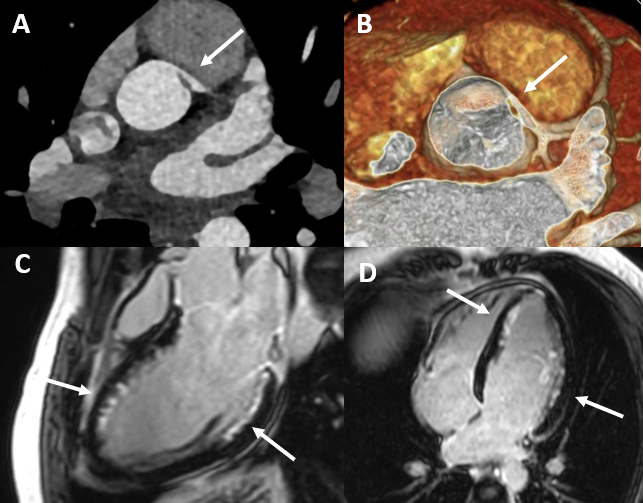

Scanner Performance

Understanding and monitoring scanner performance is essential. Critical parameters include geometric distortion, resolution, signal-to-noise ratio, and image uniformity. An example of MRI geometric distortion and image uniformity measurements are shown in Figure 2; the measurements were made using an MRI system phantom developed by NIST and ISMRM. The geometric distortion is due to nonuniform gradients, and it is important to understand both the intrinsic distortion and the efficacy of the distortion corrections, often applied after imaging. A 3D gradient-echo scan can give the accuracy of the gradient calibrations, accuracy of distance and local volume measurements, and presence and efficacy of post-scan corrections.

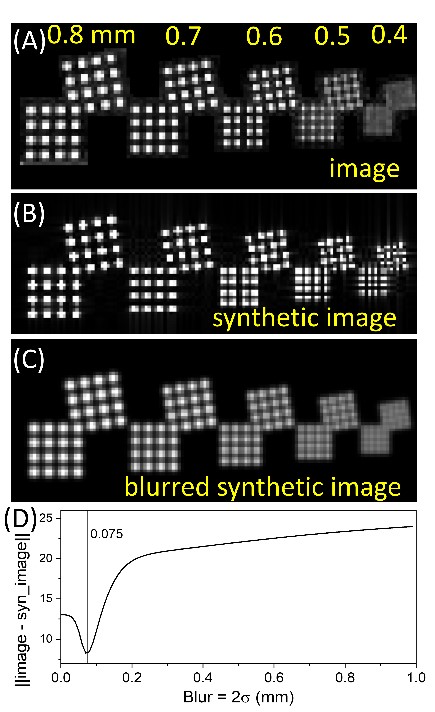

Figure 3 shows an image of an ACR-type resolution inset, along with a synthetic image: an ideal image for the pulse sequence used. Then, the synthetic image can be modified, by including blurring, to match the observed image. Protocol dependent resolution, scanner resolution, and other nonidealities can be quantified.

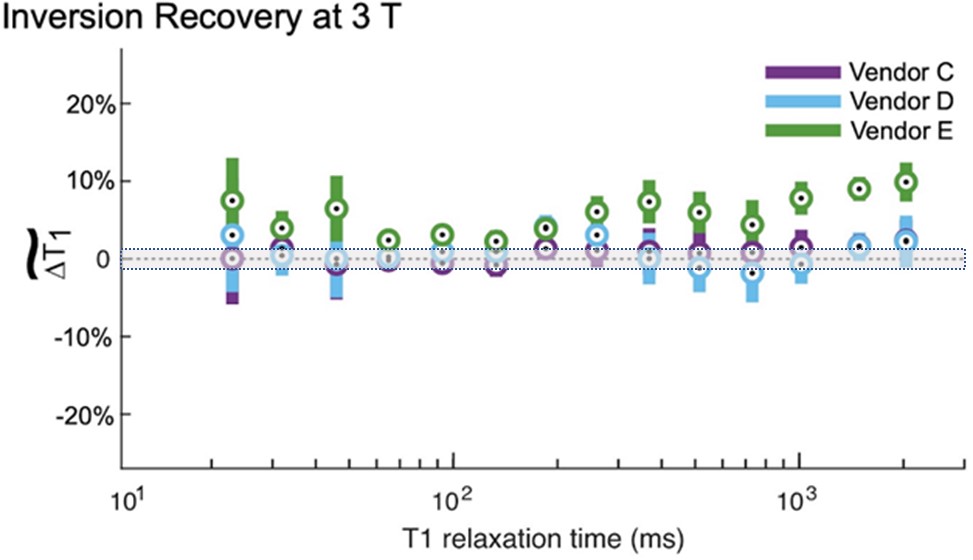

Intersite Comparisons

Intersite comparisons are critical to determine how accurately image-based biomarkers can be measured. Proton spin relaxation times, T1 and T2, are useful biomarkers to distinguish tissue types and healthy from unhealthy tissue. A recent multisite study comparing MRI T1 measurements shows considerable variation using common protocols, including an inversion recovery protocol, which, albeit too time-consuming for clinical use, is considered a gold standard. Figure 4 shows the deviation in measured T1 from NIST reference measurements, which have a well-defined uncertainty. The uncertainty defines an interval about the measured value within which there is a 97% probability that the real value will lie. One can see that there is considerably more uncertainty in the scanner measurements, and there is a vendor-dependent bias. Being able to define uncertainty intervals in image-based biomarker measurements, with traceability to the international system of units, is an important challenge for our community.

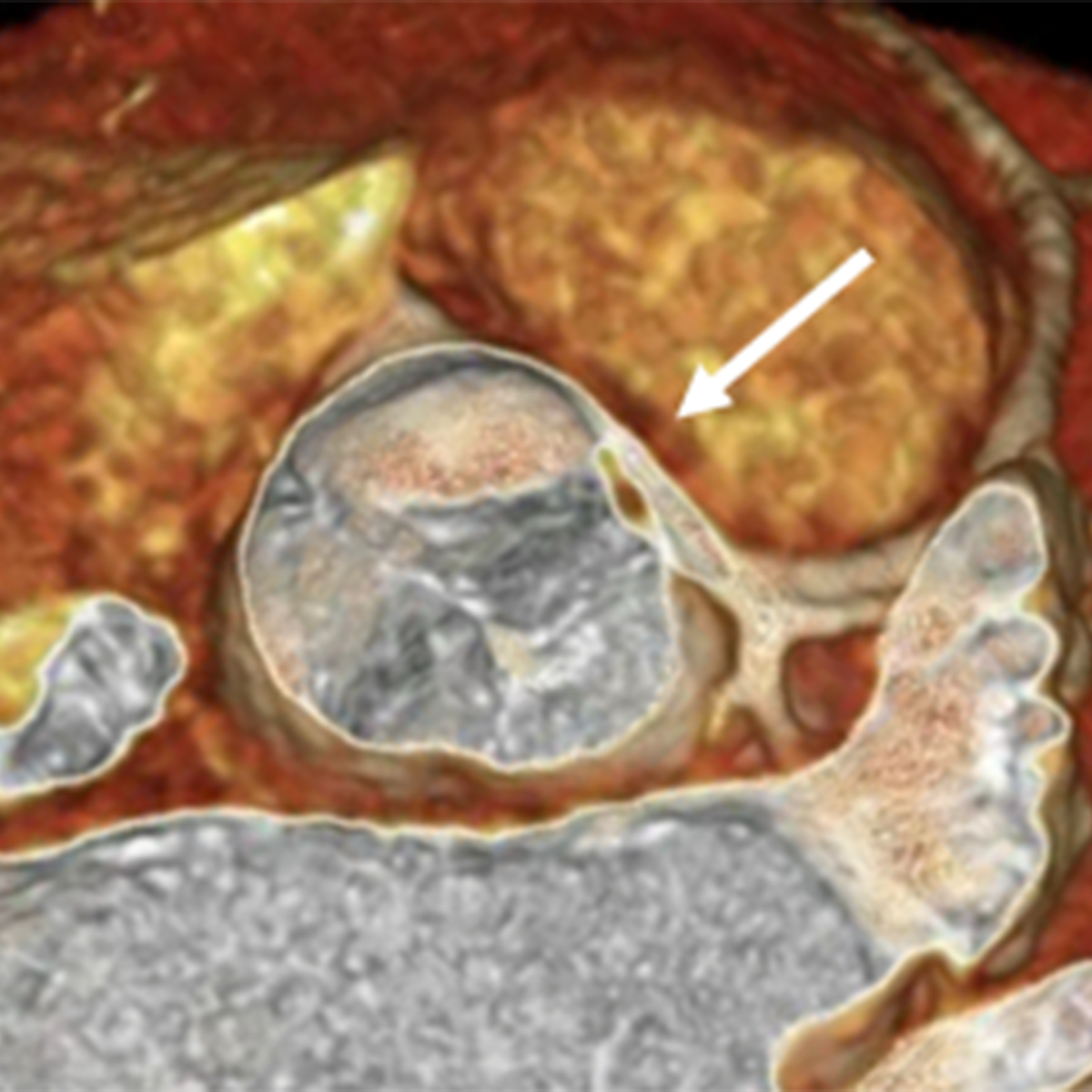

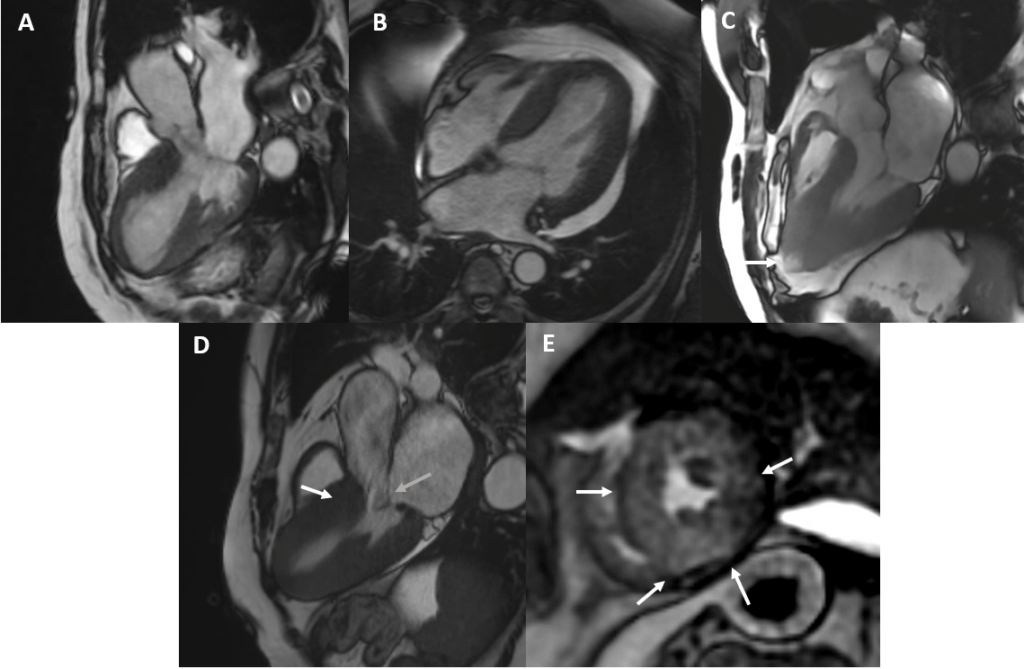

Validating Complex Biomarkers

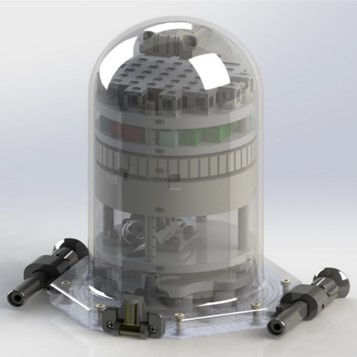

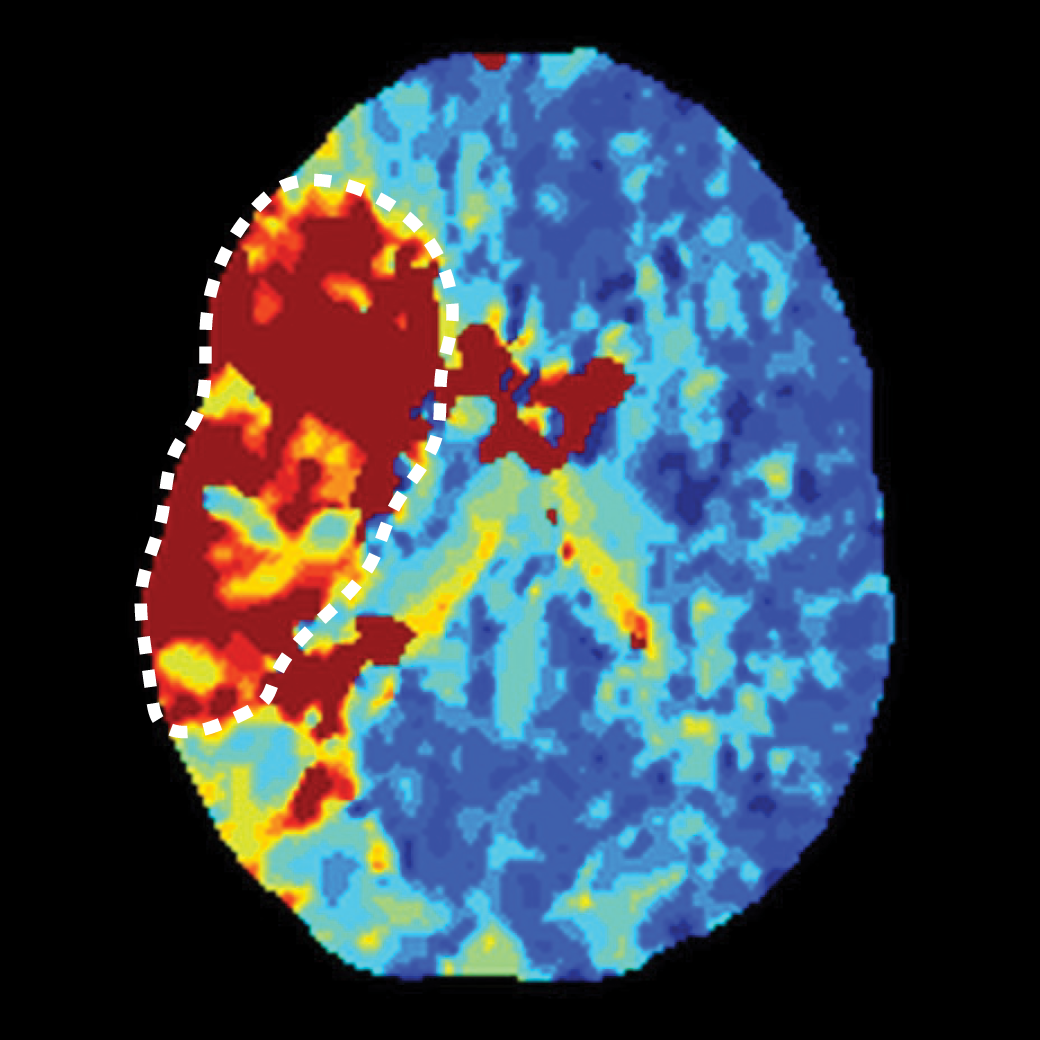

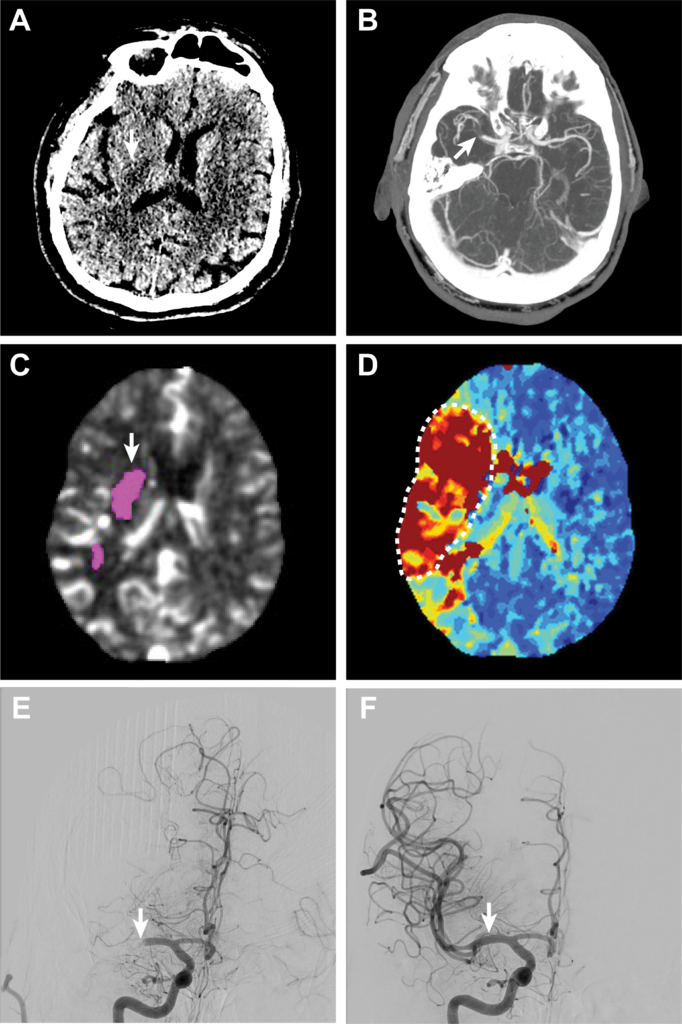

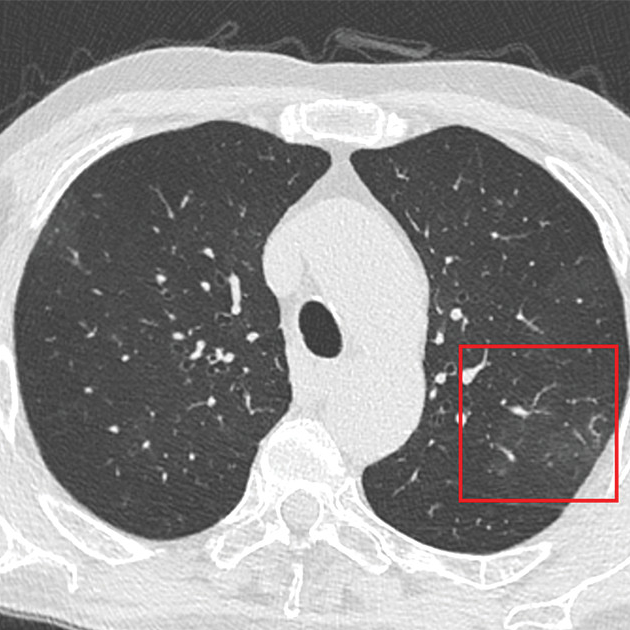

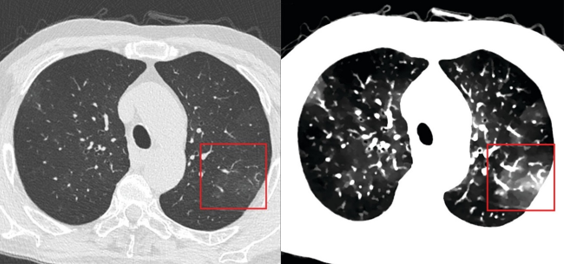

There are many complex MRI-based biomarkers, including proton spin relaxation times, proton density, fat fraction, water diffusion coefficient, diffusion kurtosis, anisotropic diffusion parameters, tissue elasticity, local concentration of metabolites and neurotransmitters, blood flow, and perfusion parameters. Diffusion-based biomarkers are a good example of the challenges encountered getting precise and useful in vivo measurements. There is a hierarchy of parameters that can be measured with increasingly complex models. The more complex models (e.g., diffusion spectral imaging [DSI]) can provide more information about underlying tissue, but validation, standardization, and implementation are more difficult. Simple models, such as extracting the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), can be very informative and useful, but limitations of the model must be addressed in the accuracy and uncertainty analysis. The phantom below (Fig. 5) contains both isotropic and anisotropic and diffusion elements to test the accuracy of many different types of diffusion-based measurements, including ADC and DSI parameters.

Phantom Lending Library

To assist clinical sites, research centers, scanner manufacturers, and phantom venders, NIST and NIBIB have established a medical phantom lending library containing calibrated traceable phantoms available for short-term loan. MRI system phantoms, diffusion phantoms, breast, and cardiac phantoms are available for loan with associated calibration documents, databases, and analysis software. Incorporation of phantoms into the lending library allows clinical and research sites easy access to phantoms, new imaging and measurement protocols to be validated on a common set of calibration structures, and phantoms to be curated with long-term stability established. Convenient access to standard calibration structures should facilitate the development and validation of improved measurement protocols and establish a framework to provide uncertainty intervals on image-based measurements.

Medical imaging scanners are sophisticated and powerful tools that can be extended to metrology systems, capable of making precise in vivo measurements of many different structural and functional tissue parameters. The work by the many institutions listed here is making this transition possible. Medical imaging metrology and standards are important components of this transition and the US medical/health care infrastructure. They often run in the background, but neither should be overlooked.