Published March 31, 2022

Tetyana Gorbachova

Department of Radiology, Sidney Kimmel Medical College

Thomas Jefferson University Einstein Medical Center

Maria Grigovich

Department of Radiology, Sidney Kimmel Medical College

Thomas Jefferson University Einstein Medical Center

Micah G. Cohen

Department of Radiology, Sidney Kimmel Medical College

Thomas Jefferson University Einstein Medical Center

Yulia V. Melenevsky

Department of Radiology University of Alabama at Birmingham Medical Center

Overuse injuries of the hand and wrist are common in both professional and recreational athletes. These injuries, also referred to as stress injuries or repetitive strain injuries, result from cumulative microtrauma produced by a combination of abnormal force, repetitive motion, and insufficient recovery time that exceeds the tissue’s ability to repair itself. These characteristic pathologic conditions may be associated with various athletic activities and most frequently occur in racquet sports, rowing, volleyball, handball, weight lifting, and gymnastics. Certain lesions are unique to gymnastics, where, in addition to performing a wide range of movements, the upper extremity becomes a weight-bearing system. This article will review overuse injuries of the hand and wrist, focusing on pathologic conditions of the bone and joint.

Stress Fractures

Stress fractures in athletes typically represent fatigue fractures caused by repetitive excessive stress applied to normal bone. Overall, stress fractures are uncommon in the upper extremity. However, several sport-specific stress fractures have been described in the hand and wrist. Hook of the hamate fracture is recognized in golfers and may result from repetitive stress or a single traumatic event from the strike of a club on the ground. In sports in which a racquet is used, hamate fractures typically affect the dominant hand; in baseball, hockey, or golf, they usually occur in the nondominant hand. Metacarpal stress fractures have been described in adolescent tennis players and most commonly involve the base or shaft of the second metacarpal. Stress fractures of the scaphoid, typically occurring at the scaphoid waist, have been reported in various sports, most commonly in gymnastics, where they may be bilateral.

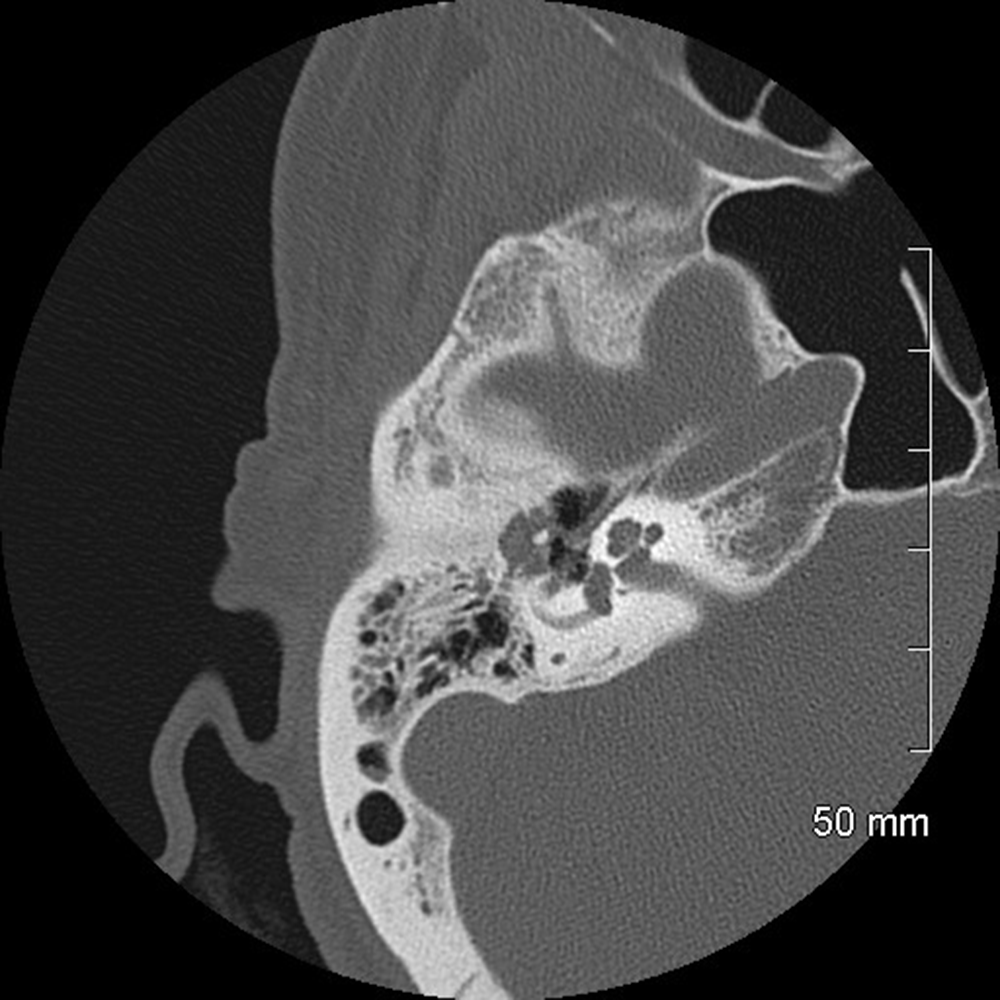

Special radiographic views can be used for the diagnosis of carpal fractures. For example, to improve visualization of the hook of the hamate, the carpal tunnel view, semisupinated oblique view, lateral view with thumb abduction, and hand radial deviation view can be obtained. CT is an excellent modality for both detection of fractures and assessment of healing. MRI may depict early stress reaction manifested by bone marrow edema–like signal without a fracture line. These changes may progress to a fracture with a low-signal-intensity line or cortical break visible on MRI.

Gymnast’s Wrist

The wrist is the most frequently injured site in the upper extremity of female gymnasts, followed by the elbow, and is the second-most common injury location, after the shoulder, in male gymnasts. In gymnastics, the wrist is exposed to multiple types of forces, which include high-impact loading, axial compression, torsional forces, and distraction. Compressive forces in particular may amount to 16 times body weight. These stressors, combined with repetitive motion and varying degrees of ulnar and radial deviation and hyperextension, predispose the wrist to higher rates of both acute and overuse injuries.

Stress injury of the distal radius may compromise the blood supply to the growing physis, which leads to abnormal cartilage ossification manifested with pain and, if untreated, premature closure of the physis, eventually leading to growth disturbances and secondary ulnar-sided wrist impaction syndromes; this spectrum of clinicopathologic findings is referred to as “gymnast’s wrist.” Adolescent athletes become symptomatic during peak growth velocity at 12–14 years old.

Radiographs show widening of the distal radial growth plate, an indistinct zone of provisional calcification, and irregularity and sclerosis of the metaphysis, the latter of which sometimes give the metaphysis a beaked or a hooked appearance. These findings are frequently bilateral and involve either the entire distal radial physis or its radial and volar aspects. Concurrent radiographic abnormalities may be seen in the distal ulna in up to 20% of cases.

MRI shows growth plate widening and periphyseal bone marrow edema–like signal. On the basis of clinical and radiographic findings, gymnast’s wrist is classified in three stages: stage I, clinical symptoms without radiographic changes; stage II, radiographic changes in the distal physis of the radius with normal radial length; and stage III, stage II with the addition of secondary positive ulnar variance. In addition to classic growth plate abnormalities, a variety of stress-related nonphyseal osseous, ligamentous, and osteochondral injuries have been described in skeletally immature gymnasts, which expand the spectrum of findings associated with the term “gymnast’s wrist”.

Ulnar-Sided Wrist Impaction Syndromes

Several ulnar-sided wrist impaction syndromes are recognized in athletes.

Ulnocarpal impaction syndrome: Ulnocarpal impaction syndrome, also known as ulnar abutment, refers to the chronic impaction between the ulnar head, triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC), and ulnar side of the carpus [16]. This syndrome is commonly seen in gymnastics, racquet sports, and golf. Athletes are particularly susceptible to this condition when excessive ulnar loading is paired with positive ulnar variance; however, pathologic changes may occur with neutral or even negative variance.

In gymnastics, compressive loads of the wrist are often combined with pronation, which doubles the load applied to the ulnar side of the wrist. Ulnar deviation combined with pronation, such as occurs in pommel horse or vault maneuvers, increases ulnar load from the normal 15% to approximately 40%. Positive ulnar variance in gymnasts may be congenital or may develop secondary to premature physeal closure of the distal radius.

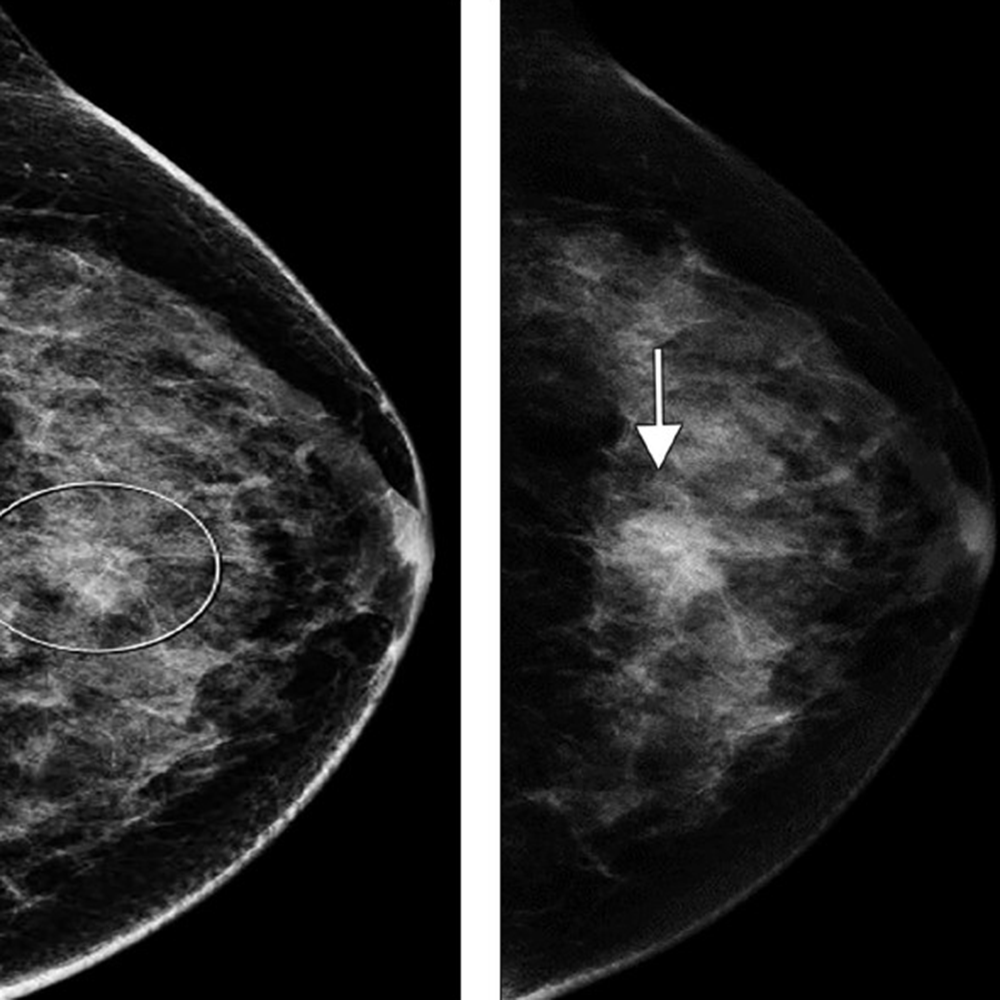

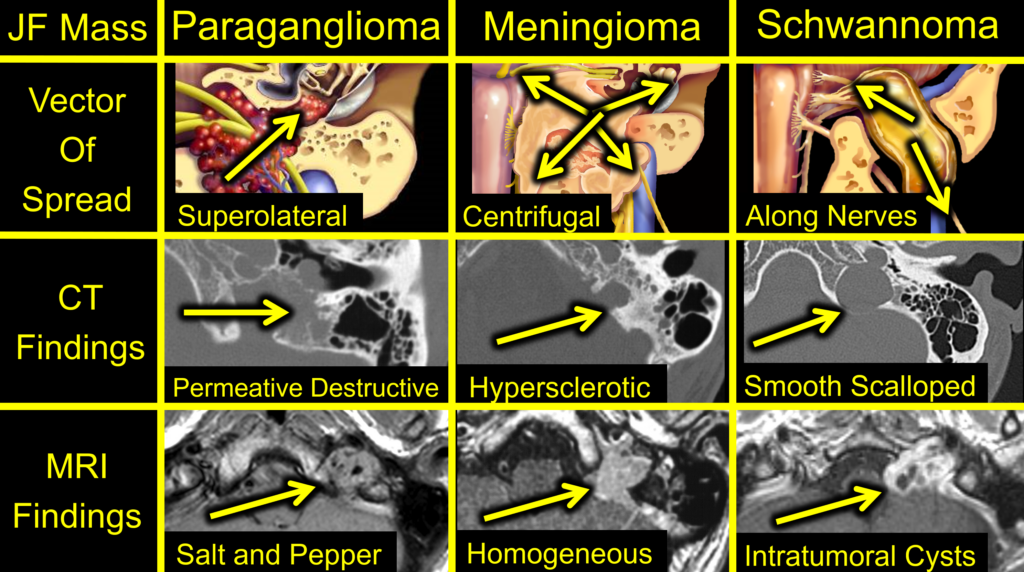

In comparison with acute traumatic injuries to the TFCC, which may affect various components of the complex, chronic ulnar abutment typically causes central degeneration and perforation of the triangular fibrocartilage disk proper, as outlined by the Palmer classification. The spectrum of progressive pathologic changes in ulnar abutment includes degenerative tearing of the TFCC, ulnar-sided chondromalacia, tears of the lunotriquetral ligament, and lunotriquetral instability—and, in advanced stages, osteoarthritis of the distal radioulnar joint and ulnar side of the radiocarpal compartment. The typical areas of cartilage loss and associated reactive marrow changes are localized to the ulnar head, ulnar side of the proximal aspect of the lunate, and radial side of the proximal aspect of the triquetrum (Fig. 1).

Radiography provides the most accurate determination of the ulnar variance and cannot be substituted with other imaging modalities, particularly in the detection of subtle changes that can be determined only by standard radiographic positioning. MRI provides detailed assessment of the TFCC, bone, and articular cartilage. MRI and CT arthrography can be used to determine the integrity of the TFCC and lunotriquetral ligament.

Ulnar styloid impaction syndrome: Ulnar styloid impaction syndrome is caused by impaction between the ulnar styloid process and the triquetral bone. It may occur as a result of congenital morphologic variations or posttraumatic and degenerative pathologic conditions of the ulnar styloid process resulting in its elongation. An ulnar styloid process is considered excessively long when the ulnar styloid process index is greater than 0.21 or when the overall length of the styloid process is greater than 6 mm. Ulnar styloid nonunion fractures may also lead to ulnar styloid impaction. This syndrome results in chronic bone contusion of the ulnar styloid and triquetrum, chondromalacia, and synovitis and can lead to lunotriquetral instability.

Radiographs may show sclerotic or cystic changes in the triquetrum, ulnar styloid, and, in some cases, ulnar aspect of the lunate. MRI detects earlier changes of chondromalacia, reactive bone marrow abnormalities, and commonly associated degenerative tearing of the TFCC.

Hamatolunate impaction syndrome: Hamatolunate impaction syndrome is related to a type II lunate that is defined by the presence of a separate facet along the distal surface of the lunate articulating with the proximal pole of the hamate. The repeated impingement and abrasion of these two bones in ulnar deviation of the wrist lead to chondromalacia at this accessory articulation.

Dorsal Impingement Syndrome

Dorsal impingement syndrome is a group of disorders encountered in sports in which repetitive dorsiflexion is accompanied by axial loading—most commonly seen in gymnasts. Impingement may result from dorsal capsulitis or synovitis with resultant capsular thickening and formation of dorsal ganglion cysts stemming from underlying ligamentous injuries and from osteophyte formation at the dorsal rim of the distal radius or dorsal aspects of the scaphoid or lunate.

Kienböck Disease

Kienböck disease is a condition characterized by osteonecrosis of the lunate. Although its pathophysiology is not fully understood and is likely multifactorial, the tenuous native blood supply to the bone is considered to be the leading cause of this disease. Variations in patterns of vascularity, such as a single palmar vessel, as opposed to the presence of both a dorsal and volar supply, as well as decreased intraosseous branching, may predispose to lunate ischemia. Negative ulnar variance has been traditionally implicated as a cause of lunate osteonecrosis due to increased mechanical load transmitted through the radial column of the wrist. However, studies and outcome data of newer treatments that do not alter the mechanical load on the lunate challenge the paradigm of causal relationship between negative ulnar variance and Kienböck disease. Osteonecrosis of the lunate progresses to bone collapse and mechanical failure of the proximal carpal arch, resulting in carpal instability and secondary radiocarpal and midcarpal osteoarthritis. In sports like handball, football, and gymnastics, repetitive microtrauma to the anatomically susceptible lunate may further compromise blood supply and lead to ischemia and necrosis.

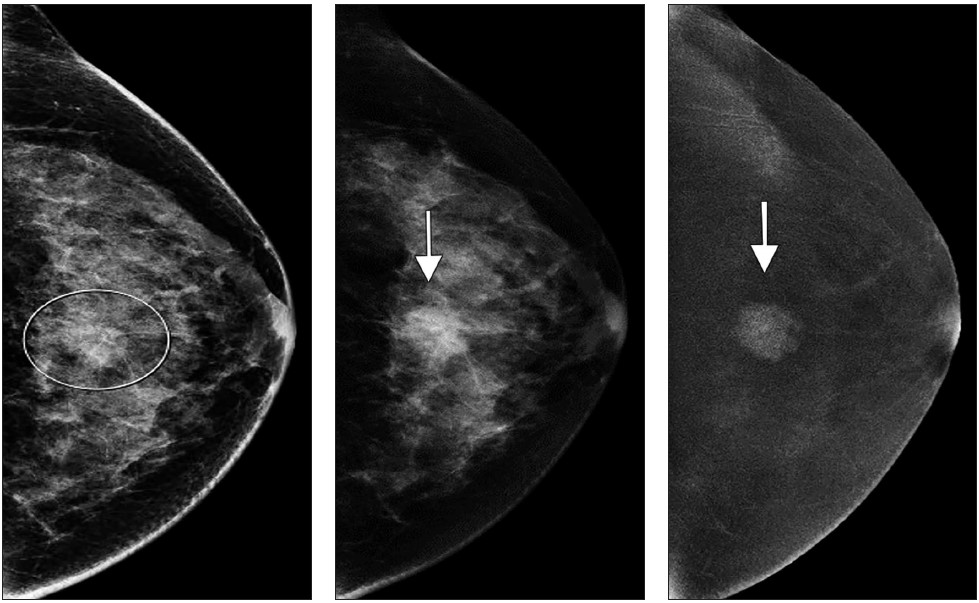

Radiographic staging of Kienböck disease is based on the presence or absence of sclerosis, lunate collapse, carpal instability, and, ultimately, osteoarthritis. MRI allows detection of early radiographically occult disease. On MRI, marrow abnormalities in Kienböck disease, in contradistinction to the ulnar-sided wrist impaction syndromes, affect the lunate more diffusely or predominantly on the radial side without involvement of the triquetrum or reciprocal findings in the ulnar head (Fig. 2).

Pisotriquetral Joint Disorders

Pisotriquetral joint disorders related to overuse include joint instability and osteoarthritis and conditions described as “racquet player’s pisiform”. The mechanism of injury is believed to be related to torsional stress on the pisotriquetral joint by repeated sharp pronation and supination movements when the racquet strokes originate from the wrist.

The semisupinated oblique radiographic view may depict advanced degenerative changes in the pisotriquetral joint, manifested with joint space narrowing, osteophyte formation, erosions, and intraarticular ossified bodies, whereas MRI shows earlier cartilage abnormalities and reactive subchondral marrow changes, joint effusion, and synovial cysts. Diagnostic injection of local anesthetic into the pisotriquetral joint may be helpful in localizing the source of pain.

Carpal Boss

The term “carpal boss” describes an osseous protuberance at the dorsum of the wrist at the base of the second and third metacarpals adjacent to the capitate and trapezoid bones. This morphologic finding may be a result of an anatomic variant, such as an osstyloideum, or may be caused by a dorsal protuberance of the third metacarpal or capitate, osseous coalition, or acquired hypertrophy due to degenerative osteophyte formation.

Acquired carpal bossing may be associated with posttraumatic instability at the carpometacarpal (CMC) joints, a debilitating injury prevalent among boxers. Under physiologic conditions, a lack of mobility at the second and third CMC joints stabilizes the kinetic chain when a punch is thrown. Repetitive high-energy forces transmitted from the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints to the CMC joints and to the wrist can result in progressive CMC instability, osseous hypertrophy, and articular degenerative changes. Chronic avulsive injury by the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) tendon on the unfused osstyloideum has been proposed as a possible mechanism of painful carpal boss in hockey players. Both congenital and acquired carpal boss may produce symptoms related to chronic mechanical irritation of the overlying structures, manifesting as ganglion cyst formation and tenosynovitis.

Carpal boss may be depicted radiographically when implementing a modified lateral view with 30° of supination and ulnar deviation of the wrist; CT provides the most detailed evaluation of osseous anatomy. MRI is an optimal imaging modality for depicting regional osseous and soft-tissue anatomy, particularly osseous fragmentation, reactive marrow changes, and variations of the ECRB tendon insertion.

Boxer’s Knuckle

Boxer’s knuckle is a disruption of the sagittal band of the extensor hood with subluxation or overt dislocation of the extensor tendon. This is a closed type injury of the extensor mechanism that may occur both from acute trauma and from chronic repetitive microtrauma. The clenched-fist position, coupled with the great forces generated by punching, renders the MCP joints susceptible to injury [24, 26]. Injury can encompass an extensor hood tear, injury to the joint capsule, synovitis, and, in advanced cases, severe secondary osteoarthritis of the MCP joint [24, 26]. Sagittal band injury in boxers occurs most frequently on the radial side of the index and long fingers, resulting in ulnar subluxation of the extensor tendon; however, variability exists in the injury pattern, particularly in the index and little fingers.

Ultrasound evaluation shows tissue swelling over the MCP joint, partial or complete discontinuity of the sagittal band, and dynamic tendon subluxation. MRI depicts morphologic changes indicative of the insufficiency of the sagittal band such as poor definition, focal discontinuity, or focal thickening, as well as arthritic changes in the MCP joint.